Аўтар: Volha Rybčynskaja, 12/12/2014 | ART Cult Aktivist interview

WAR WITNESS’ ARCHIVE

The interview with the project’s author and curator Aleksei Shinkarenko

PROJECT BACKGROUND. DRAMATIC PERSONAE

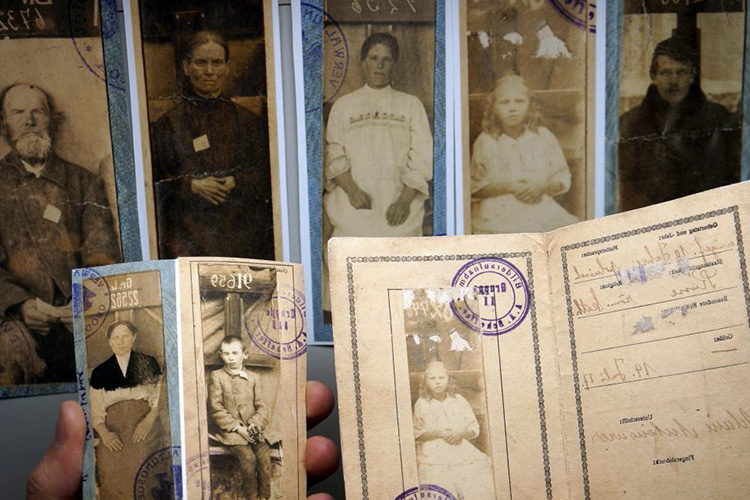

The project «War Witness’ Archive» emerged as a response to the global trend of referring to history, of reinventory of the memory about the last century events rich in wars, disasters and conflicts. When getting acquainted with photographic and historical archives of World War I (the Great War) visitors become participants of a talk about tragedies of the past and present. They form their attitude, interpretation and evaluation of the events which both date back one hundred years and happen presently.

© War Witness’ Archive

Volha Rybčynskaja: What did such a deep and serious project which transforms the viewer into the participant and the visitor – into the witness, into a source of a many-voiced version of history, interpretation and construction of the scenarios for the future, start with?

Aleksei Shinkarenko: Launching the first exhibition («Belarus in World War I») can be recalled as one of the project’s preliminary stages. It was made in cooperation with the National History Museum and, in fact, the museum delegated curatorial duties to a guest curator, and in that case — to the entire organization, the Center of Photography, which was an experiment for both the museum and for us. Confidence appeared and we did our best to made use of it. It was very important that we were given the opportunity to use our own methods of search and analysis while working with the collections of photos stored in museums all over Belarus. The fact that we were supported by the National History Museum helped us significantly.

V.R.: That is they shared a topic with you and later on you fully developed it — from the methodology and research strategy to the project’s implementation inside the museum’s space?

А. Sh.: Exactly. Inits turn, the National History Museum acted as a very good partner. In terms of partnership it was a real experiment: on the one hand there was a curator with his own creative team and methods, on the other – the museum with its high status and scientific basis, its contacts and networking. I think that it was exactly this which inspired us to take further steps. At the level of research we managed to go through the impressive amount of data. It was important for us to make a well thought out exhibition, a sincere statement dedicated to the events of World War Iin Belarus. To do this we obviously had to let the topic go through us, to live it ourselves. And this experience added to that knowledge and empirical data that were obtained in the course of research, while we were looking for and collecting the materials, as well as while developing the topic and discovering where and what was stored, of what type or nature photographic evidence was made available.

I personally had to experience such a state when I was made a witness myself getting that unique opportunity to hear the voice of people who you see only in pictures and to actually give them my own voice.

V. R: So, did you, as a curator, give the topic your own interpretation?

А. Sh.:I definitely did. As a curator, as the author of the concept and the visual narrative, I practically put myself in the shoes of the war witness. I was telling stories adding my own interpretation to what I was observing. Obviously, I was summing it up, somehow matching it with the historical context.

V. R: Does it mean that you built up your own narrative, adding not only photo graphic data, including the data you got from the front, but also other types of documents and evidence? What was important here? What was given the priority?

А. Sh.:There was a significant direction that was set by the National History Museum, a humanistic component, to be exact. We did not touch upon political or military issues, did not go into the concrete matters of war actions, tactics or strategies. We were more interested in how these actions affected people. Would we be able to trace among the archive photographic materials the evidence of what was happening to people who were living here at that time and who actually became hostages of the war they had nothing to do with? Finally, one story was formed out of various pieces, a narration focused on a person who found him/herself in the center of the conflict and tuned out to be its victim. Practically, we managed to visualize history, to create an album, arranged and represented according to the line of the historical events of the beginning of the ХХ century.

© War Witness’ Archive

V. R: So, you created a certain general picture, mise en scene – a theatre of war. However «Belarus in World War I», from the point of view of historiography, is an incorrect name, since at that time Belarus as a state did not exist.

А. Sh.: Moreover, I was consciously defending this formally incorrect name. I see the point in clear matching of concepts and contexts, like chasing words that work with our consciousness as a kind of a slogan. It is a call to recognize that it is our history. Indeed, we can build up complex structures of the names and explanations: «World War I on the territory that now is known as the Republic of Belarus».

But I am sure that nowadays it is very important to articulate the message by means of a phrase that will not push this history away from us, but will bring it closer. So I match the nonexistent within the same field.

The title conceals a lot of codes, just like the ornament used in the exhibition design. It is important for us to draw the viewer’s attention to it. We are interested in his/her own interpretation of these combinations of words: World War I and Belarus. At the same time we suggest a supporting visual construction which provides a basis for their own impressions, opinions and thus allows them to witness the course of history, the catastrophe that occurred here, in the territory, which turns out to be unknown for many. And this very moment of surprise is something which I often came across when accompanying the exhibition and observing the audience’s reaction. That is what I would call a starting point for the project «War Witness’ Archive»

V. R: So, the viewer’s reaction was an important component of the project. And how was the perception of the archive formed? Was another approach necessary?

А. Sh.: In the historical project «Belarusin World War I» I personally experienced and observed people’s reactions. Something was really happening to the visitors – something that gave them an opportunity to start speaking about this history. During the visits, inside «WarWitness’Archive», we often explained the viewers that photos could silently remain in the collections of the museums, but then they could use your voices to speak. Thus we were showing what cooperation (reaction) we were expecting from the viewer. Someone needed additional tools to get the context actualized, others intuitively referred to their own experience, cultural knowledge and genuine human reactions. In any case through empathy people became war witnesses.

© War Witness’ Archive

CONTEXT CODE: FROM HISTORY TO PRESENT

V. R: How hard was it to shift from the historical topic stereotype? The first question the journalists asked you was why you decided to show the World War I archive in the Museum of Modern Fine Art?

А. Sh.:I believe that we are gradually moving towards a broader understanding. We are speaking about the conflict, about a possibility of an artist, a curator and a author to form an antiwar statement and if yes then what sort of statement it could be. We are reflecting on the ways of how to call a man to prevent wars, to become aware of the consequences that are always the same, that is – disappointment, devastation and pain.

V. R: That is the cycle is repeated. Primarily, the historical one.

А. Sh.: Especially, if we talk about our territory. We have it encoded genetically. Some sort of fatality. We have recently been to Stockholm dwelling on the topic of World War I. It was very curious to observe the Swedish people forming their exposition of the wars of the XX century without actually being engaged in them for the last 300 years. They have a completely different rhetoric and interpretations.

V. R: What do you think, if the project were put into another situation, into the international context, to what extend it would be possible to implement it?

А. Sh.:Indeed, there is a question: is it possible to present within the global space a project which is locally directed at deciphering its own understanding of fatality and at refuting it? We talk about archive as about something that works with the local. Can it be turned out into the general global perception? The Swedes, for example, have their own understanding of the war, their own attitude to it, about ten generations of them have not been involved into it and all their actions are aimed at multiplication and saving, at caring about people.

Whereas we have the war imprinted into our minds since childhood, from movies and stories to annual parades and victory celebrations.

Jula Hiejsik, Darja Amialkovič, Oleksandr Michied, Aleksei Shinkarenko © War Witness’ Archive

V. R.: Perhaps for this reason some of the project’s participants are right saying that it is we who are responsible for having the war stuck at our genetic code. Their main message deals with the fact that artists, writers, film directors and creative people in general romanticize war, they create a beautiful image and aestheticize the catastrophe. As a result an image is created which is then replicated. The Soviet times coined most of the stereotypes, the military heroic past, World War II.

А. Sh.: Therefore, there is an interest in the World War I archive — since we have not gone through it yet, there are no super structures and additional layers. And you can talk about it whatever, unattached, as about an archive which has not developed any stable reaction to itself yet. The photographs are also quite specific there, the photographer was involved, he was not a professional, a photojournalist yet. Thus, this archive is unique, it gives you the opportunity to empathize on your own, without relying on multiple interpretations. It is hard to say if it would also be the topic for the global audience. I think this is at least a reason to have the issue raised. For me it is obvious that the project has become timeless.

But will it be such outside the geographic boundaries? When we look through the materials on the topic of wars in Asia, in Afghanistan or Iraq, we still understand that this is not our war. It happens somewhere far away, in the media.

© War Witness’ Archive

In the project we talk about a European type of war, where there is a deep trail of World War II, but there are also deep trails of World War I. It does not matter if it was the Eastern or the Western front, Northern or Southern — all the same it was a pan-European catastrophe, in which everybody found him/herself in the same conditions: occupation, refugees and injuries were everywhere. Would we be able to feel all this looking at the pictures? Talks about what has been done in your own house always touch people and we feel it in people’s reactions. And now I wonder whether this reaction can move to the universal human level, when you are shown what has been done in the house of another.

Will it be our common home, at least making use of the mainland criterion? Or is there any peripheral area where the wars that occur are not taken into consideration? This question arises when we go out of the local.

Interviewed by Volha Rybčynskaja. Translated from Belarusian by Volha Bubič

Opinions of authors do not always reflect the views of pARTisan. If you note any errors, please contact us right away.