Аўтар: Tania Arcimović, 20/06/2015 | ART interview

YULIYA VAGANOVA: MUSEUM AS AN EXAMPLE OF CIVIC POSITION

pARTisan #27’2015

Despite more than a century-old history, today the National Art Museum in Kiev is a unique platform that clearly articulates not only its artistic mission, but also a civic position, which is an extremely rare thing, especially in the post-Soviet space.

On the one hand, like any other institution of a similar format, the museum continues to preserve and collect the best examples of Ukrainian art. On the other hand, it is increasingly developing as a platform for the implementation of innovative projects related to contemporary art practices. For example, the Fashion Day organized by contemporary artists-activists Alevtina Kakhidze and Albina Jaloza or the creation of Maidan Museum — such projects are more characteristic of independent cultural initiatives or contemporary art museums than of national institutions. That is being topical, being present here and now, especially in the course of significant historical changes in the country is seen as a part of the Museum’s current mission and this turns to be an inspiring example of how a contemporary museum can develop and position itself: to become a space of solidarity, the meeting place of generations, attitudes and communities.

Yuliya Vaganova, the deputy director in charge of exhibition work and international links, a participant of «Time Machine – Museum in 21st century» program, speaks about the political turmoil influence on the Museum’s activities, about the ways of keeping a balance between traditions and innovations and about the reaction of the Ukrainian public on the «experiments» set.

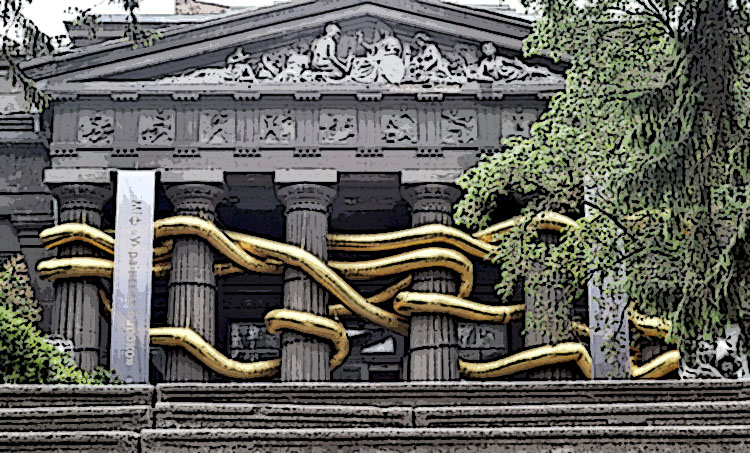

Instalation by Olga Milentiy. Myth Ukrainian Baroque art project. 2012. Curators: Oksana Barshynova (NAMU), Galyna Skliarenko (freelance curator)

— Yuliya, frequently state national museums are seen as quite conservative traditional institutions that are unlikely or quite slow in reacting to geopolitical developments around. Many people who work in similar institutions insist on such an «archaic» autonomous role of the museum, building a distance with «here and now». In this regard, your Museum seems to be an exception. Or is it, in principle, determined by the changes that have occurred in Ukraine over the last year?

Yuliya Vaganova: Of course, the changes that are taking place at the Museum are associated with the processes that occur in the Ukrainian society. But it would not be quite right, in case of our Museum, to talk about them as about a sudden event triggered by an external factor or context. Moreover, if we keep in mind the Museum’s unique history. Changes have always been characteristic of this place, and when we look at our projects today, we realize that the founders’ idea that lay behind this institution’s concept in some kind of a mysterious and constant way comes to the surface.

Founded in 1899, the Museum initially was established as a public institution. It was not some emperor’s or private person’s collection, which was planned to be commercialized, and then it became a museum. Neither was it a church collection. This institution was established by citizens: over 50% of the funds were given by the city dwellers. Yes, they were philanthropists, but their number was really big. They came together, realizing that the city had a need in such an open institution. In my opinion, this thing is important for current understanding of the Museum’s history. Furthermore, I think that the processes that began inside the institution in the 2000s are very significant, too. At that time the Museum was participating in various programs, including a large-scale program «MATRA», which certainly influenced the professional level of the people who were working there. A wave of new projects, including those related to contemporary art, started, a new team was formed, which miraculously reflected a balance between experts from the old school of classical art education and young critics, who were already working with contemporary visual theories. And to date, the average age of the Museum employees is 35 years, which, of course, is indicative of a national institution.

This is how a new understanding, a vision of the museum and its place in the society were gradually formed, attempts to discover the common points with various societies and communities were made. But the turning point, in my opinion, was the story of a change of the Museum administration at the end of 2011. Then one director who had been in charge of the museum for about 10 years left his post. Another head was appointed who came from the commercial sphere of galleries and had no experience in managing such institutions; moreover that director’s objectives were at odds with the employees’ expectations. This brought a wave of protest inside the Museum, and despite the fact that in those days one could easily be dismissed, the confrontation started and it lasted almost for a year. For example, the colleagues from the education department led excursions wearing a white armband or a band around their forehead with the words «I protest». And this is how they held their excursions. That protest was impossible to be suppressed.

At that time the professional community also supported the Museum organizing smaller protests, and thus the Museum managed to defend its position.

Employees of the museum put on masks in disagreement with the laws of January 16. Kiev, 2014

A competition was announced to fill in the director’s position, and it was done for the first time in the Museum’s history. Although it failed, Mariia Zadorozhna was appointed as a new director. She had been working at the Museum for nearly 20 years, she knew the staff and the collection, and therefore, knowing the problem from the inside, she started paying much attention to the creation of the atmosphere in the team. The team was really important for her where everyone could get self-realization. This is how we faced Maidan.

— Does it mean that for the Museum the Maidan events did not become a conceptual turning point? Was the Museum already different then?

Y.V.: It would rather agree with it. Already before Maidan the Museum made some projects innovative both for itself as for a national institution and for the society, which marked the upcoming changes. For example, «Draftsmen Congress» initiated by the Polish artist Paweł Althamer at the Berlin Biennale in 2012. The project’s essence was in having the Museum allocate some space on its walls where everyone could visually express him/herself. One could draw, paint over what had been done by others, completely paint the walls with white, etc. Various groups were invited to participate in the project, including the artists who were put into rather uncomfortable positions, since their work was presented as equal to the work done by any visitor. Due to this fact some artists even refused to participate.

— When Maidan started, here in Belarus while reading the latest news we were impressed by the actions that the Museum staff headed by the director performed. For us it was a real example of solidarity and a possibility to act and make a difference inside a small professional community.

Y.V.: Yes, when Maidan started, the Museum director was the first to realize that no member of the armed forces was to enter the Museum. Secondly (and this happens to be the most important thing), we were not supposed to remain locked inside the building, we were to go out and start a dialogue with «Berkut» and other military people. Then the Museum turned to be located in front of the barricades, completely surrounded by «Berkut» and other internal troops, and our task was to show that the building was not empty, that we were inside it. Everything was happening intuitively, but we understood that the dialogue was necessary.

In my opinion, the whole situation in Ukraine is the result of twenty years of silence, the absence of ordinary human communication between people.

And I think that the dialogue with the military forces — the fact that we went out to them, asking them to push the barrels with fire away from the fence of the museum, not to put on fires on the Museum’s facade, to clean up after themselves — did work. Because, for example, the collection of the Museum of Kyiv (which was stored in the Ukrainian House) was partly destroyed when «Berkut» entered. We managed to keep the Museum. Only once an officer tried to enter the building, but our director banned him to do it, she did not let him in. He threatened her with the tribunal, and she replied that in such a case we would write a letter of resignation, and then they would have to settle this issue with other people. As a result, no one came into the Museum.

Behind the back of the museum’s founder Mykola Biliashivskiy is a tent of Berkut. Kiev, February 2014

It is also important to note that the Museum became an example of self-organization, an example of civic protest even before the start of Maidan. I mean the story with the change of directors: how the professional community got together at that moment, and it turned out that defending our position was possible. A similar example of self-organization was at the times of Maidan, when the Museum was taking all the decisions on its own. The Ministry of Culture and the Presidential Administration did not respond to our letters when tires in front of the facade started to burn. Practically, we were abandoned and had to come up ourselves with solutions on what to do and how to behave in that situation. Thus we addressed the Ministry of Emergency Situations directly and they agreed to give us two militaries in the event of fire or other emergency situations. Of course, we also asked Maidan protestors to keep in mind when throwing Molotov cocktails at our side that still it was a place where the best collection of Ukrainian art was stored. We asked them to put down burning tires, because the smoke was penetrating the Museum and could damage the works of art. That is why we removed the collection from the ground floor and hid it in the funds to protect it from the smoke. We were partly heard and several days later the tires stopped burning.

— And how did the Museum continue to live after Maidan?

Y.V.: After Maidan the Museum found itself in a confusing situation. Of course, all the projects were cancelled. We could not take the responsibility for international projects, our exhibitions were also cancelled. There was a situation of hard times and hesitation.

Nevertheless, it helped us react differently at what was going on: responding here and now and doing it as honest as possible, trying at least intuitively to search for topics that would get a feedback from the community.

The first project that we made was «Codex of Mezhyhiria» — an exhibition which displayed objects from the Yanukovych’s residency, which we happened to have at our disposal by chance. The thing is that when the protestors entered the residency, many of them realized that looting might start. A group of museum staff was formed, including the employees from our Museum, whose task was to make a list of those objects. And since we had free rooms on the ground floor, everything was brought to us. Mass media began to write about it actively, and we realized that we could not but display those objects. The only question was — how can we do it? For the post of the exhibition’s curator we invited the contemporary artist Alexander Roitburd and two young architects as specialists in expositions, and together they managedto find a trick. At the same time the project «Our Way to Independence» was launched which contained photographs of the barricades in Riga in the 1990s. And within the same space of the ground floor there was an exhibition of the French photographer Eric Bouve: he showed the photos from Maidan. Thus, a certain route the viewer had to follow to see the exhibition of the Yanukovych’s treasures rose naturally: implying that at the initial and final stages one had to go through the photos from Maidan. I remember a story of one visitor who having met the Museum director in the hall told her: «It is my first time in your museum. I have come here to see the art, to enjoy and relax. And what are you doing? You are intentionally driving me crazy!» For me it is an important comment.

Пасьля двух месяцаў вымушанага перапынку супрацоўніца музэю ўстанаўлівае на барыкадах шыльдачку з запрашэньнем у музэй. Кіеў, сакавік 2014.

One more thing happened within the same period: children’s attitude to the Museum changed. We have a small kids area which formed thanks to Althamer’s project and somehow we decided to keep it. If earlier kids drew some of their impressions of what they had seen in the Museum, caused by their thoughts and moods, then suddenly drawings started to appear reflecting the events that were taking place outside our walls. They contained Ukrainian symbols, the topics of war and defenders. We did not offer them such themes, it was as if the kids suddenly realized that the museum was a place where they could bring external reflection or discuss what was going on outside. It is one more significant sign for us.

That is, last year was difficult, but at the same time promising in a way that the Ministry did not «force» us to make any projects, we were free enough in making our decisions. This also poses some danger, because being free you need to understand what you show and what you reflect on, you must accept more responsibility. Especially if we take into account the situation in the society and in the country on the whole.

— But your example is an exception for the post-soviet space. How do you manage to find the right balance between conserving traditions and the innovations?

Y.V.: We do our best in developing several directions. First of all, we alter exhibitions, for example, after showing a rather traditional exhibition we display an exhibition of contemporary art. We had a project about Maidan, then there was the project «Places» about Malevich Award laureates. Later we opened an exhibition of Anatoly Sumar, a Ukrainian artist of the 1960s. Thus a formal balance was kept. But again I must emphasize that this process has already been evolving since the 2000s.

Visitors to draw in the museum during the Congress painters project. May 2013, curator Paweł Althamer

Secondly, what seems more interesting to me personally, we are trying to work with our own collection: to show it not chronologically, but to disclose certain topics with the help of the works. If previously we were just talking about the 18th century art, now we are attempting to highlight some significant issues within a specific period — Ukrainian Baroque or the genre of portrait, for example. Or, when talking about some artist, we focus, in particular, on his/her personality, showing the civil or artistic viewpoints. So far we have been trying to do it through additional projects and lectures.

What concerns working with the private collection, last year in December we had a project «Heroes. An Inventory in Progress», which turned out to be a unique experience for us. A situation when the Museum attentively goes through the whole collection that it possesses — from ancient icons to the 20th century works — only to create a large-scale project on a specific topic has never happened before. In addition, the project has become a platform for communication between the Museum staff; it brought together in one team the keepers from different departments. They were not just working with the own collections, but were also producing comments on other custodians’ choices.

— Is the project background connected with the Maidan events that gave rise to the topic of today’s heroes?

Y.V.: The idea came before, exactly thanks to the project «Time Machine – Museum in 21st century». Two years ago in Berlin we met with the professor and curator Michael Fehr and invited him to come to Kiev. At first we thought he would just hold a series of workshops, but eventually we decided to make a full-scale exhibition project about the heroes.

But, of course, the stimulus for such a topic was the situation in Ukraine, when new heroes started to appear here. You probably know the slogan «Glory to Ukraine! Glory to the heroes!» After Maidan the discussion arose whether we should recognize those who died in Maidan and those who are fighting now in the Eastern Ukraine as heroes and in what way it should be done then. Should they be awarded the title of Hero of Ukraine or not? Since this title, as you know, is rooted in the rhetoric of the Soviet Union and is politicized. As a result, we came to the idea in principle to try to uncover the topos of «hero», «heroism» and «heroism» on the background of the history of Ukraine (before the country got its independence in 1991) to show that the figure of the hero is closely associated with temporal context — social, cultural and political.

Together with the audience we would like to reflect on the definition of a feat. For what great deed and who becomes a hero? Who proclaims a person to become a hero? Who and under which circumstances is proclaimed to be such? What are the differences between the heroes and saints, heroes and martyrs, heroes and leaders, heroes and «stars»? What are the typical elements of the visual language that can be determined when identifying the heroes in different epochs? Where do they come and how do they change? Are heroes needed today or the society can live without them? The exhibition features eight rooms, but we leave the last one empty for the viewers’ reflections, for the deconstruction of heroism and today’s heroes.

— My final question is about the creation of a museum dedicated to the Soviet past, the idea of which increasingly appears in the post-Soviet space. Do you think such a museum is really needed and what it might look like?

Y.V.: Of course, it is necessary. But it is important to identify and define the subject correctly. If we mean only the Soviet aspect, we automatically ignore many other topics and our understanding of the Soviet. It is important not only to reflect on the past, but also to understand what common themes and concepts have emerged in this space. It is needed in order to understand how we can affect it and in which way it can be used in future.

Therefore, I see such a museum in the form of a fine balance. And it is important to try to go beyond the geographical boundaries: to look for parallels and common points in the histories of other countries, other communities. Then you may be able to understand how to work with this trauma. For example, in some countries there are museums which deal with the issue of Soviet occupation, of course they are necessary, but they use a pretty simple language. Perhaps the first step may be like this: how many people died or sent into exile and for what reason, etc. But when observing the situation in perspective, this approach deprives us of a possibility for further development. Revealing the facts is just one part, it is really important, but it is not the only one.

The time is changing rapidly, and if we do not manage to find the correct form of how this theme can be developed, it would close up again into a sort of a capsule and the wound would remain, thus we would not have the problem solved.

Splitting this topic into different vectors is significant, as well as reworking this experience, giving it a way out. I do not know how to do it, but at the level of intuition I see it in this way.

Interviewed by Tania Arcimovič

The translation into English is abridged.

Photo © NMMU archive

Opinions of authors do not always reflect the views of pARTisan. If you note any errors, please contact us right away.