Аўтар: pARTisan, 20/07/2015 | ART Cult Aktivist interview

ART AS ANTHROPOLOGY: COOKING TOGETHER

This year in June the artistic residence at «Ў» Gallery of Contemporary Art in Minsk welcomed the artists from Georgia — Nini Palavandishvili and Data Chigholashvili. As a result, in the gallery backyard they set up a public kitchen — anyone could bring their own home recipes and together with the artists and other citizens cook, treat and exchange with one other one’s culinary experience, and most importantly — their stories associated with these recipes. For Minsk such an experience of direct private and immediate interaction between the artists and public is still rare. Although, obviously, in such projects there is a lot of potential not only for making artists and public get closer and understand each other better, but also for the artists themselves to go beyond the gallery sites and learn more about the problems, interests and subjects the contemporary community has.

Nini Palavandishvili and Data Chigholashvili share their impressions about Minsk and its citizens, about the relationship between cooking, contemporary art and public space, as well as about contemporary art in Georgia.

Data Chigholashvili and Nini Palavandishvili. Minsk. Photo by V.Ščarbakova

Nini Palavandishvili: Informally «GeoAIR» platform was launched in 2003 growing from the project «Foreigner» made by the Georgian artist Sophia Tabatadze. Then she was studying and living in the Netherlands, and she had an idea to come with her friends to Georgia and to do something here. In 2006 in Tbilisi she made the project — «Georgia Here We Come». The artists from the Netherlands came, they collaborated with Georgian artists and eventually organized the exhibition. Afterwards Sophia began to plan how to establish an organization, and in 2007 together with another artist Nadja Tsulukidze she registered «GeoAIR». Before I had been living in Berlin for 10 years, I returned and started looking closely what was happening here, I met Sofia, and thus I joined the «GeoAIR».

We decided to start with the creation of an archive of contemporary Georgian art. The fact is that when we came back to Georgia, there was no information about artists— in terms of who was working with contemporary art practices, what exactly they were dealing with, in what forms — nothing at all. So, a group of 6-7 artists, art critics and curators got together and began to collect the archive. Simultaneously with that we organized presentations of the artists we collected information about.

It was also a new form of communication between the Georgian public and the artists — to talk about contemporary art, why it is art and what forms it can take.

In 2010 we decided to open the residence. From the very beginning, many of our projects were made in collaboration with international artists, and when they came, of course, there were those who wanted to stay longer, to understand the context better, that is, to make process-oriented projects. And this was how the first residence appeared in Tbilisi, which had its own program and was functioning throughout the whole year. So at the moment we have three interrelated activities — projects, residence and archive. We try to integrate guest artists into our projects or to develop projects in partnership with them.

— So, «GeoAIR» was founded not by theorists — curators and art critics — but also by artists? In Belarus the situation is similar: the main initiative belongs to the artists.

Data Chigholashvili: Yes, our theorists are still not so active as artists, it is true. For example, we are collecting the archive library at «GeoAIR» which everyone can use. Practically next door to us there is the Academy of Arts, we constantly invite its students to visit our library, but the interest is not very high. Recently our colleague Katharina Stadler, who lives and works in Tbilisi, founded the NGO «Concept and Theory — Tbilisi» to work in this direction. We hope she will succeed.

N.P.: We have very few theorists. Georgia creates more art than it has time to analyze. Reviews often simply state facts or copy press releases. Of course, we are interested in changing this situation. Now we have agreed with one of our colleagues, who teaches at the Academy, that they would include contemporary Georgian artists into the semester curriculum and would also use materials from our library. The program will start in September.

D.Ch.: I should add that important reflection within the project is also necessary for the artists themselves. For example, I work with site specific practices and interdisciplinary field where art and anthropology overlap. Naturally theory plays an important role here. There are artists who think that working in interdisciplinary areas has become a sort of a «trend». But without understanding nothing but a form imitation is obtained. Certainly, there are examples of very interesting projects that work and experiment with different practices and forms, but they are still not numerous.

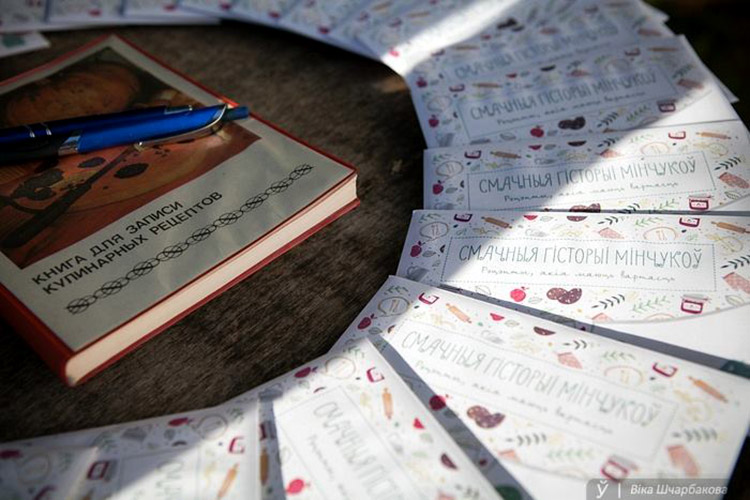

During the public cooking. Minsk. Photo by V.Ščarbakova

— What happens in your country in the field of education in contemporary art practices?

N.P.: Education is very conservative and academic at state higher education institutions. Those who are interested in learning more and getting a high-quality and comprehensive education, choose private schools or move abroad. For example, Vato Cereteli, who founded the Center for Contemporary Art in Tbilisi and opened there an informal contemporary art school. At our private university we also have such a department. But self-education, discussions and debates probably still remain the most important ways.

D.Ch.: We try to include students from different educational institutions into our projects, also attracting people from various disciplines. In December, we had an anthropologist at our residence, he organized a workshop and showed different films, discussing them with the workshop participants, various theories were presented. The discussion was attended by artists, psychologists, anthropologists, sociologists — a good interchange of knowledge took place. And as a result of joint work they created a short experimental film «The Rhythm of Everyday Life: Stories of Tbilisi Migrants», in which all the participants gave their vision of the migrants’ life in Tbilisi.

N.P.: From the very beginning the research component of the residence has been important for us.

We are not interested in making formal projects, we carefully approach the environment where we live and work in.

— The project you implemented in Minsk — namely, the interaction and involvement of the audience, or rather, the city residents, is rather rare for our context. But before we talk about the way you worked here, tell us about the experience of similar projects in Georgia. How do the locals perceive your initiatives? What do you have to face?

D.Ch.: Certainly, there are some difficulties, but I see them as a part of the working process. Certainly, in the beginning there is always an idea of how and what we will do, but it does not always turn out the way we want, and we must be ready for it. We often face the fact that our activities are not perceived as art, they say: where is art here? You are social workers (also a worthy and important profession, in my opinion,) but not artists. That is, conservative views remain, but still something is gradually changing.

N.P.: Undoubtedly. For me, any theme has always been closely linked to the place where it is implemented. And when I started to do projects outside the white cube and art institutions, a lot of questions appeared: why am I showing my works in the underground passages, or, for example, in an abandoned cafe in Batumi, where there a mosaic that remained from the Soviet times? Why didn’t I pick up a clean nice place? I tried to explain it, to talk to people, because collaboration and understanding are possible only through communication. And speaking of projects outside the traditional space, now, in principle, it has become even fashionable to do them in such places.

The place becomes even more important when working with social issues or with the subject of communities. It is clear that if you go out into the public space, you cannot do in it whatever you want, because the space already belongs to someone else. If it is a park, there are people who walk in it or play with their children.

And we must bear in mind that they want to understand how they use this space, to enter into a dialogue with various groups. Yes, we face a lot of obstacles, but we always try to talk to people. It is a long process, but it is moving on.

During the public cooking. Minsk. Photo by V.Ščarbakova

D.Ch.: That is why I think that anthropology begins to work with contemporary art. Working with people and making works about people are one of the important aspects of division, from the very beginning one should think about how (s)he wants to invite the public to take part in the project. Therefore, I see a lot of potential in such an exchange.

— How many projects related to the direct interaction with the people do you implement?

D.Ch.: Now, perhaps, we do only such projects.

N.P.: But it all started with the project on migrants. Prior to this, we can say, there were simply artistic interventions.

D.Ch.: Yes, the topic of migration appeared two years ago. And it all started with a pilot project within the festival in one of the districts of Old Tbilisi — Betlemi. We knew that for a long time people of different nationalities had been living there, one could encounter a Georgian Jew and a Georgian Armenian there. We were curious to talk to them, to see how they live, and to do so through their national cuisine. Anthropology and the Academy of Arts students collaborated with us. All together we conducted field work, interviewed people, held discussions and cooked meals, built relations and printed publications. During the festival, our members cooked the same dishes for the visitors, they treated the guests with them in their yards, and at the same time the volunteers had an opportunity both to try the food and to talk with the «chefs». For us it was a good experience, and we decided to continue working with the theme of migration, cooking and public space in Tbilisi. We organized such a common public kitchen with migrants, when together with them we cooked and they talked about their life in Tbilisi, about problems they face. It turned out that there are a lot of stereotypes about «good» and «bad» migrants, there are cases of racism. But many people do not even realize it, they do not believe that this could happen in Tbilisi.

In addition to the publications we were shown on TV: we participated in a culinary talk program where we came together with migrants and cooked together, whereas they were talking about their lives. We also worked with children at schools: they did visual stories about their neighbors who live in their area. Before that, we taught them to use cameras, as well as basic knowledge of photography, visual arts and ethnographic methodologies.

N.P.: That is, we tried to reach various audiences: some people watch TV, others read newspapers, school is in general quite a different space.

D.Ch.: In our opinion, food is a marker of our identity, it says who we are individually and collectively. Thus, cooking turned out to be that very form and manner through which people can open up and get closer to one another. For example, a person comes to the park and sees some people cooking there and talking about something. There can be your neighbor, as well, whom you do not know very well, he is cooking something and you just join him. This is how the process of involvement begins. Thus you learn to have a lot of stereotypes about those people, and generally they are the same as you, with similar problems and joys.

Of course, we never had any illusions about our projects’ scale. Like we never hoped to eradicate racism completely through them. But it was important for us to raise this issue at least a little bit, and I think we succeeded.

For me, art does have such a potential — to reveal something, to make a lot of things and problems visible.

During the public cooking. Minsk. Photo by V.Ščarbakova

— And where it is easier to implement such projects — in Tbilisi or abroad? In bigger cities or in small towns?

N.P.: In many ways, it all depends on people. If I wanted to do a project in the area where I live, I would be difficult, since my childhood I have known that context and have been watching it. Obviously, many things have changed, and first of all I will have to find like-minded people in order to work with local people afterwards. I am sure there will be many obstacles, including the fact that they know me from childhood. Outside Tbilisi or even outside Georgia sometimes it is easier: there is a different approach to you there — you are a tourist, a stranger, and here another trust appears. In Georgia, they will first meet you with a question: why are you entering my area? Why should you know my stories? Then, when you start talking to them, you explain your idea, and other relationships are formed.

— How do you assess the project made in Minsk? Was it different from those set in Georgia? Was it easy for Minsk dwellers to get involved?

N.P.: It should be said that the idea to implement such a project in Minsk does not belong exclusively to us. Last year Valancina Kisialova and Hanna Čystasierdava from «Ў» Gallery of Contemporary Art visited us, and we started to talk about a possible organization of our visit and the residency in Minsk. Then we asked them which topics or issues may be relevant. And then it turned out that in the gallery, which has already been working at that place for six years, communication with the neighborhood has not developed yet. And if to think about future residences, of course, it is important.

We began to think, how to attract the neighbors, to get them interested in what is going on inside the gallery. Initially we had an idea to do this through the children who live here and play at the playgrounds and in the yards. To talk to them, for example, and to collect their grandmothers’ and mothers’ family recipes as well as stories around these recipes. But, as we mentioned at the beginning, it is not always possible to have everything as it has been planned. A problem appeared: on the first day, when we were going to do such a meeting with the children, no one came. It turned out that there were not so many children who play in that area. Maybe because holidays had already started by then and children had left the city, I do not know. We came up with a new plan. We printed out invitation cards with a welcoming text and wrote there a Georgian khachapuri recipe.

D.Ch.: The concept of the project was to gather not just Belarusian recipes, but people’s home recipes. Therefore Nini wrote not a traditional khachapuri recipe, but that of a cheese khachapuri — her family one.

N.P.: Exchange was important for us: we give you a khachapuri recipe and we would like you to come to us and share your recipes with us. And we need to thank Vika Ščarbakova, who was helping us and came into every porch of the neighboring houses to invite people and talk to them. But unfortunately, they did not react, though they did say that it was interesting for them. Time was flying and we decided to include into the project the whole city of Minsk and invite Minsk residents from any city area to share their home culinary history. The meeting was held in the backyard of the gallery «Ў», we cooked our dishes together, telling stories about them and asking people to tell us their own ones. We collected about 20 recipes, some people could not be present at the meeting personally, so they sent their recipes by mail.

D.Ch.: We always say that any city is its people. But it is important to look at the city also through personal stories.

Even through the cuisine: a hundred years ago people used to cook other dishes, family stories were also different, but now there are vegetarian recipes, Thai, Italian ravioli — it does say a lot about many things.

During the public cooking. Minsk. Photo by V.Ščarbakova

N.P.: In the set we left one postcard empty, and if there is a mood and willingness, one could write a recipe of one’s own and its story and send it to the gallery. At first we thought, well, there would be only draniki recipes. And suddenly we discovered a ravioli recipe, because that person was in Italy and he really liked this dish, so he learned to cook it. In such a way stereotypes imposed on us by ideologies disappear, for example, that in Georgia people constantly eat khachapuri or khinkali and in Belarus — draniki. In my family we do not eat khachapuri every day at all, only on holidays. Moreover, the change of generations, social and political changes affect culinary traditions.

Thus this method of communication — through cooking in company — helps us to know more about the city and its inhabitants.

— What was your first impression about Minsk? What would you recall of it? Were you surprised with anything?

D.Ch.: Unlike Tbilisi everything is quiet and slow.

N.P.: And meditative. I was struck by the number of green areas, parks, we really lack this. On city streets there are many cyclists.

D.Ch: Of course, we understand it is only a primary superficial impression. If you get to know more about the context, you start seeing and living in the city differently.

N.P.: But the main thing, of course, is socializing with different people. We met your artistic community, and saw that we had a lot in common — the same position of young artists, the problem of space, current topics. For us, this is all very close and clear.

D.Ch: Yesterday during the discussion about the museums the Stephan Wackwitz’s idea was articulated where he called the museum as a society’s self-portrait. I do not agree with this, everything also depends on the context. So first of all it is necessary to talk to people when you come to a new place, it will tell you more about the society.

N.P.: During the yesterday’s discussion we talked a lot about the post-Soviet space, and I thought that especially if you start working with it, you understand how artificial this mix of people was. Yes, they were united by the Soviet Union, but all these people — Soviet citizens — were so different: different mentalities, cultures, languages and now a political direction in these countries is different. Of course, there are some common themes with which you can work, share experiences, but why should one artificially find them?

We need to communicate more to make ideas for projects and cooperation arise from direct live communication. But not because the task is set — to do something together.

Special for pARTisan, June 2015

Opinions of authors do not always reflect the views of pARTisan. If you note any errors, please contact us right away.