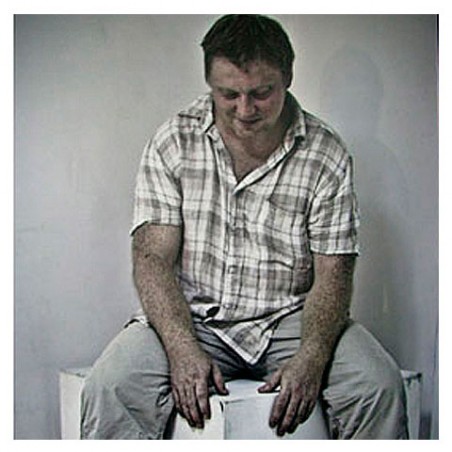

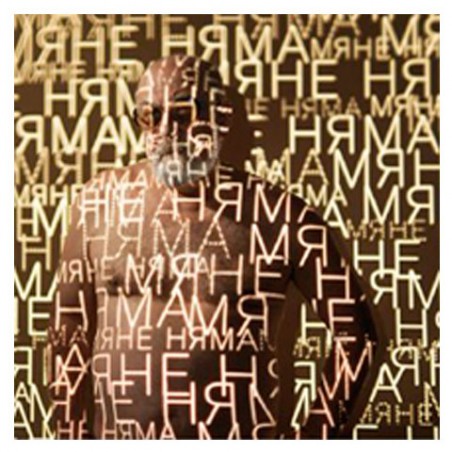

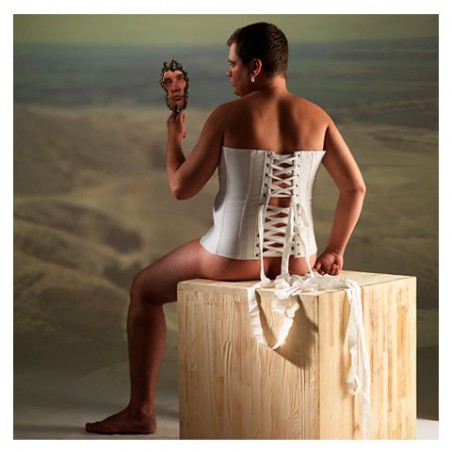

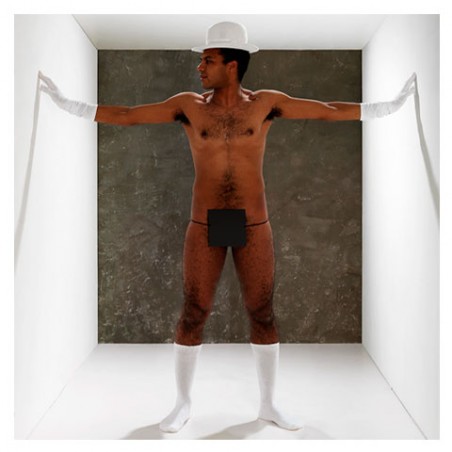

Ihar Łohvinau \ photoproject Living People by Igor Ganza

Valancin Akudović \ pARTisan’s project The End of The Words

Juras Barysiević \ pARTisan’s project The End of The Words

Seviaryn Kviatkouski \ pARTisan’s project The End of The Words

Artur Klinau \ pARTisan’s project The End of The Words

Andrej Chadanović \ pARTisan’s project The End of The Words

Andrus Takindanh \ pARTisan’s project The End of The Words

Vital Ryźkou \ pARTisan’s project The End of The Words

On 3 February the bookstore ‘Lohvina’Ў‘ (Minsk) celebrates its 3-years old. pARTisan also send our’s greetings and wishes long fruitful and inspired working years.

© pARTisan #19’2012

From the beginning Logvinov publishing house staked only on Belarusian-language literature. What was the reason for that? Obviously, this is not a profitable project.

Ihar Łohvinau: By that moment, I quit my job at the publishing house of the European Humanities University and was thinking what to do next. In principle, I realized that my only skill was to publish books. ‘What books and where?’ I was thinking when I got introduced to the young Belarusian writer Zmicier Viśniou and ‘Bub-Bam-Lit’ (a Belarusian literary movement, founded in 1995, which focuses on post-modern European literature. — Author’s note). I got infected by the ‘drive’ of those crazy writers. It was an allusion to some kind of Belarusian Silver Age. I felt like inventing some insane things, even with no value to anyone, in order to unite a large number of people and make everyone feel happy.

I wouldn’t say I was a big fan of Belarusian literature. I grew up in the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic where the language was either urban or rural. Belarusian was a rural language. Later, I realized that was a mockery of culture, and that I became a “product” of this genocide. Therefore, it was the energy and enthusiasm of Bum-Bam-Lit writers that kick-started the Logvinov Publishing House.

Was it easy to launch a publishing project in 2000?

I.L.: If you feel the ‘drive’ that I talked about earlier, it doesn’t matter what difficulties you may encounter. When we started up, we had no financial support. All we had was enthusiasm.

I felt like Miklouho-Maklai, because I had to be a pioneer and learn from my own experience. In terms of procedures, Belarus, perhaps, is the most difficult country to open a publishing house.

However, I was surrounded by many people who were interested and ready to offer support. I believe, that was the reason why everything worked.

Apart from enthusiasm, was there any hope that Belarusian-language literature could become a profitable business?

I.L.: A book publishing project implies generating income. However, to me, it was not about business. It was about the authors who tried to do something in the first place, and that was interesting. Revenue generation was of secondary importance.

On the other hand, Belarus lived in the epoch of ‘great illusions’ in the early ‘00s, and national self-consciousness was on the rise. Everything was boiling, and you felt like everything was about to change. At the end of the day, nothing really happened, and the epoch of “large disappointments” came. Nevertheless, a lot of projects, good and useful for Belarusian culture, emerged in that period of great expectations.

Belarusian literature finds it difficult to reach the Russian or Western European book market. Very few authors have succeeded. For instance: Alhierd Bacharević with his Saroka na šybenicy, Viktar Marcinović with Paranoia, Artur Klinau with Malaja padarożnaja kniżka pa Horadzie Sonca. How can you explain the fact that Belarusian literature is not in demand by foreign readers?

I.L.: Closedness is one of major illnesses of our literature. This is a kind of literature that, in my view, is unable to create a new meaning. Belarusian authors do not get involved – sometimes deliberately – into the global context. They should stop repeating their mantra: ‘We, Belarusians, are miserable people subjected to cultural genocide’, etc. It’s like scratching a wound.

As Alexander Ivanov (director of the Russian publishing house Ad Marginem. — Author’s note) put it, literature is a story that touches people. The majority of our writers seem to be lacking an inner literary need for creating stories. They have a desire to present themselves and work for the ‘national project’. Yet, they have no desire to be convertible and understood by other people. In my view, Belarusians got consumed by their ‘wound-scratching’. As a result, they got estranged from the world.

However, the world has changed. It appears that the problem of nationality is relevant only to Belarus. Belarusian literary men seem to be stranded in the national consciousness that emerged in the 1980-90s.

They don’t understand that in the rest of the world the problem of language is replaced by the problem of the reproduction of meanings. When I got involved with the literature written in Belarusian, the Belarusian language was an important reference point. This is a totally different language; it is organized in a totally different way.

It struck me when I learned that it was very easy to translate Heidegger and Kierkegaard into Belarusian, because the thinking and the structure of both languages match. It is much more difficult to translate, for instance, German authors into Russian; translators have to look for compromises. So, the Belarusian language gives a possibility of creating a ‘message’ understood by all Europeans.

That’s why back in the ‘00s we thought that with the help of the language, the new vibrant generation could create something new. When nothing worked out ten years later, we were not much disillusioned, but we came to the understanding that the Logvinov Publishing House had turned into some kind of a locked-in project. Nobody knew for how long it would stay this way.

Is it a problem of the Belarusian language, which remains unclaimed in Belarus, or is it about the content of our literature?

I.L.: I think it is all about closedness. On one hand, local authors have strong anti-Russian sentiments. On the other hand, they do not wish to work under more stringent requirements in Europe, spending more energy and making a greater effort. There is no environment, no competition in Belarus. Since Belarusian writers do not earn high author’s fees, they have no motivation. Our book market consumes only 1,000 copies of Belarusian literature. One can’t shape a policy of the publishing house on this.

Supporting small literatures by the state makes more sense. This type of economy is viable in all countries where small publishing houses receive up to 70% of funding from the state to support national literature. It is non-existent in Belarus though.

State-run publishing houses like ‘Mastackaja Litaratura’ actually get subsidies from the government to publish Belarusian-language literature. It is only that your interests or your authors do not really converge.

I.L.: The state naturally ‘feeds’ its ‘state ones’. No country in the world – besides maybe China – runs state-owned publishing houses. It is very expensive and difficult. Why would the state need to subsidize book publishers? The state only needs to support national culture, so it creates national programs and foundations.

It makes no sense to compare this to Belarus, where cultural policy is based on the ideological divide, when the interests of the president, the government, or some corporations are the state’s number one priority.

Therefore, Belarus keeps the loss-making state-owned publishing houses, which execute government-guaranteed orders for literature that serves the interests of power. Those publishing houses may employ wonderful people and print good books, but it is absurd to have book-publishing organized in this way. To publish a book, one has to get ideological clearance: they see if the author is loyal, if he or she went to the square (large-scale protests against the official results of the presidential elections in 2006 and 2010 — author’s note). That is, ‘friend’ and ‘foe’ identification overrides sense and national pride.

Let’s take the story of Uładzimir Arłou as an example. Here is a contemporary Belarusian writer of genius who can be comfortably called a national asset. Ten years ago, after yet another political or personal conflict, he was told that he would never be able to have his books published by any Belarusian state-owned publishing house. How do you take this? Of course, we publish his books.

On one hand, Belarusian literature fails to fit into the global literary context due to the ‘closedness’ that you mentioned earlier. On the other hand, the literary industry is obviously non-existent. Authors cannot earn a living from books they spend years to write. Moreover, they have to finance their own books’ publishing and take care of their distribution. Why, do you think, does this ‘literary Ghetto’ still exist?

I.L.: There are many reasons for that. Firstly, the Belarusian-language literary market is in the process of formation, and it is expanding very slowly. The 2007 statistical data showed that only 7% of books were published in Belarusian. This was already a strong indicator. I don’t think much has changed today. All depends on the consumption market capacity. The majority of population reads in Russian. This is the second part of the problem. How can an author earn a living, if his works are not profitable, and his matter is of no public importance?

But I repeat the process of Belarusian-language literature expansion happens, because of the new generation of students for whom the Belarusian language is becoming the language of freedom. Still, in my view, it is too late for the emergence of national self-consciousness, because this problem no longer exists for the rest of the world. There are problems that concern corporations, transnational colonies, but not some nations.

Could you say that in order to escape from this ‘ghetto’, Belarusian literature should leave aside the priority of the national and focus on the variety of genres, authors, and content?

I.L.: Yes, it should focus on the creation of meanings in the first place. Using national or ethnic trends in literature is difficult. It is much more productive to use semantic trends.

At any rate, literature is about meaning, story-telling, and aesthetics. Besides intellectual fiction literature, there are crime stories, romance novels, and books for children. The language of writing is not so important.

The main thing is that this literature is born from the Belarusian language, which creates very important opportunities. A representative example is Ales’ Razanau, the author whose works form incredible poetry anthologies. In my view, he can be compared to Paul Celan. Ryazanau describes simple things with masterful detail and depth. He creates a special meaning, which I can’t fully understand yet. This is born from the Belarusian language. The same may be done in prose as well.

How does the Łohvinau Publishing House manage to survive then, especially in the current harsh economic conditions?

I.L.: Despite having no money and no clear picture of the future, we continue to live happily and publish books. We have some more or less profitable projects. The books by Andrej Chadanović and other writers of the new generation sell well. However, they account for only 5-10% of our operation. By and large, we are moving ‘by feel’. As for our publishing house’s book series, we are again testing waters. For instance, Gallery Y, led by the writer and philosopher Ihar Babkou, publishes the writings that may claim a significant place in literature. Their authors are: Valancin Akudović, Ihar Babkou, Anton Franciśak-Bryl’, Aleh Minkin, Natalia Charytaniuk and others.

This year, we plan to launch the ‘Y ‘bookstore series, in which we will republish the most significant books of Belarusian literature and culture over the past two hundred years. We will pay special attention to the literature of the ‘80-90s ‘renaissance’ ages. The series will be edited by the Belarusian philosopher Valancin Akudović.

In your opinion, what are the prospects for Belarusian literature?

I.L.: I think one needs to wait for a new generation. Some are already emerging, like Natalia Kharitaniuk with her recent 13 stories about a dead cat (the winner of the Maksim Bahdanović Debut’2010 independent Belarusian award in Prose. — Author’s note). Vital Ryźkou’s The Doors which are closed with keys (the Debut’2010 award in Poetry. — Author’s note) and Anton Franciśak Bryl’s translation of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Smith of Wootton Major (the winner of Debut ‘2010 award in Translation. — Author’s note).

That is, despite my personal fatigue, I think Belarusian literature has a future. Perhaps it will be different from what we imagine now.

The young voices that continue to break through and sound persistently are a good sign, at least for me.

Interviewed by Ales’ Barysiević. Translated by Dorota Stachura.

© photos by Igor Ganza; pARTisan #10’2010 special issue

Opinions of authors do not always reflect the views of pARTisan. If you note any errors, please contact us right away.