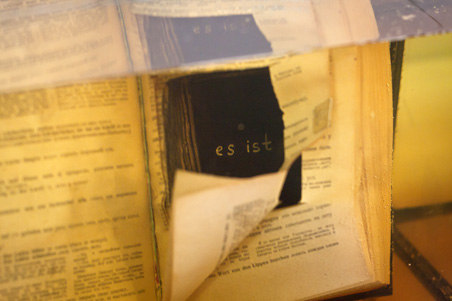

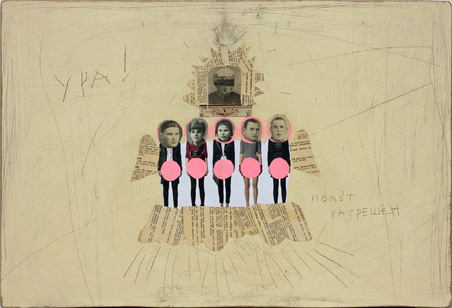

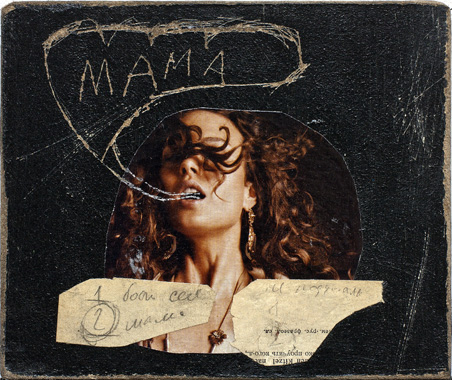

Antanina Słabodćykava It’s Here project \ Gallery Ŭ, Minsk 2012

Antanina Słabodćykava It’s Here project \ Gallery Ŭ, Minsk 2012

Antanina Słabodćykava It’s Here project \ Gallery Ŭ, Minsk 2012

Antanina Słabodćykava It’s Here project \ Gallery Ŭ, Minsk 2012

Antanina Słabodćykava It’s Here project \ Gallery Ŭ, Minsk 2012

Archive! © Published in pARTisan #09’2009. Translated fragmentary

The hackneyed cliche, ‘A scar makes a man more handsome,’ determines what degree of bodily injuries is found acceptable, as a mark of courage and manliness. A scar on a woman’s face or body is a mark of ugliness. Society gives two opposite verdicts on one and the same thing.

J. L. Nancy summed up a complex relationship between the self and the body in a paradox, ‘I never know my own body, nor do I ever know myself as a body… But I know others as bodies.’

In different cultures people walk, sit, stand and position their bodies differently. The whole humankind can be divided into two groups: those who squat to take a rest and those who sit on some kind of object. The squatting position may seem ridiculous to us, but it is quite normal for Orientals and inmates of Soviet hard labour camps and prisons.

Certain bodily movements can be deemed a taboo or disgrace. However, ‘good bodily manners’ can be absolutely inappropriate in a different culture, so bodily movements are socially constructed and culturally determined.

…

Autoagression can also be caused by traditions and certain religious beliefs. In Ancient Greece women mourning for their relatives used to cut off their hair and scratch their faces and necks so that they bled. In Assyria and Armenia women scratched their cheeks as a sign of mourning. Scythians mourning their king’s death cut their hair, cut their hands, scratched their foreheads and noses, cut off parts of their ears and put an arrow through their left arm.

However, severing some parts of your body can become just a common practice. We are all engaged in bodily modifications when we cut our nails or have our hair cut. In Belarus, there is a tradition of undoing the bride’s plait.

Thus, human body was viewed as a space to be marked with ‘social signs’. Tattoos, artificially reshaped noses, ears, necks and limbs, as well as circumcision used to symbolise that a person belonged to a certain kin, group or caste. An individual is not just born but ‘made’ and ‘carved’. Through bodily modifications, an individual seeks to fit into society and state their position in it.

…

Today an alternative image of ugliness and misery is emerging as a reaction against the regulated glamorous world of beauty.

A woman is particularly apt to be ‘cruel to her body’, since by injuring herself she tries to deny her body as imposed on her by society. She attempts to avoid being inscribed into the society, so as to protect and keep intact her own self, so unique and imperfect.

However, capitalist society can turn anything into a commodity to be sold on the market by creating demand for a seemingly unique product. You cannot find just a shampoo in a shop, there are shampoos for dry and oily hair, long and dyed hair, for dark, fair and red hair, but there isn’t just a shampoo. This creates a false impression of uniqueness. Of course, being so ‘unique’, I need a ‘unique product’.

…

Leaving your town, you can do a long way and endure a lot, you can lose sensitivity to pain altogether, you can knock incessantly at the gate of another town till it opens.

And you can live there, step by step losing your memory and memories. Meanwhile, your own town will be gradually falling apart, brick by brick, each of them unique in their own way, so that once they are lost, they cannot be regained.

…

Today’s advanced technologies create new bodily organs. We get so used to them that if we leave a mobile phone at home we really feel as if we lacked a limb. It all leads to a kind of fragmentation of the body, which could be dismantled, complemented with some new parts and then reassembled.

Alienation from our own bodies makes us resort to pain as the ultimate instance that can bring back the reality of the body. I return myself to myself, tying myself with red threads of scars to a disappearing substance, unable and unwilling to keep up with what is going on. I would rather not be than be like that, but if it is gone, I will be gone, too. Realising that, I catch my body by the hand, keep it and ask it to stay with me.

…

The town I live in is in some ways similar to other towns, but it certainly has its unique colour, shape, layout and architecture. It took me quite a time to realise that

I am its chief architect that it is only up to me to decide on its future, to approve of or turn down any reconstruction project or removal of certain buildings and monuments.

It is up to me to decide who is welcome to my town and can stay there and who will never get a visa. It can be very difficult to love the town you live in, but it is here that love of yourself and the town of your body begins.

Volha Hapejeva. Translated by Volha Kalackaja

© photos by Antanina Słabodćykava

Views expressed are those of the authors and may not reflect opinion of the editors. If you note any error, please contact us right away.

Uses of visual materials are permitted andprohibited by the Copyright Act.