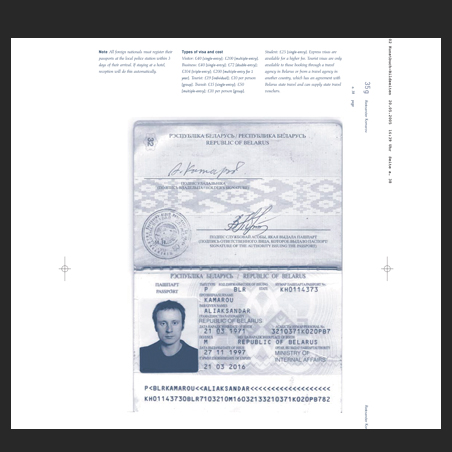

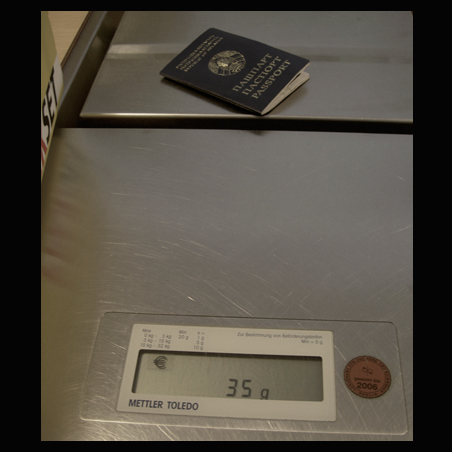

Aleksander Komarov 35 grams

Aleksander Komarov 35 grams

Aleksander Komarov Estate

Aleksander Komarov Estate

Aleksander Komarov Palipaducienne

Aleksander Komarov Palipaducienne

Aleksander Komarov Palipaducienne

Aleksander Komarov Palipaducienne

pARTisan #24’2013

Aleksander Komarov is a Belarusian artist, who now lives in Berlin. He works with various forms of media, primarily, with video.

He took part in numerous international projects in Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, Japan, the Czech Republic, Turkey and other countries. In 2010, his film A Psi geographic Research was shown at the Y Gallery within the framework of the joint Belarusian-Swedish project “Visual Arts. New practices” (the curators were Hana Ćystasierdava and Martin Schibli). In the same year, his work “The Palace” participated in the joint project of Belarusian artists “Open the door? Belarusian Art Today” guided by the Lithuanian curator Keystutsisa Kuyzinas (Vilnius-Warsaw). In 2012, within the framework of the Belarusian part of the project “Europe (to the power of) n” at Lena Prenz’s curators’ exhibition “To West of the East” held at Y Gallery, his two films Palipaducienne and Language Lessons were shown.

Aleksander, last year you visited Minsk twice. What are your impressions of the city? Has it changed?

Aleksander Komarov: After I left Belarus, I visited it several times, but only for a couple of days, so it’d hard to say. What has changed for me personally is that my trips to Minsk have become professionally oriented; these are not just trips to visit friends and relatives. Lena Prents has also made an influence, as she began to invite me to participate in various Belarusian projects. Thus, I have established contacts with other artists; there emerged interest to “films”, namely, the very form I’m working with now. The notion of “film” used to be associated with the concept of a fiction or a documentary, but in the context of contemporary art it looked new.

However, last time in Minsk your films Estate, Palipaducienne and Language Lessons were shown within the exhibition “To West of the East”.

A.K.: Now I basically work only with films. These projects are, of course, more long-term project starting with the definition of the concept, search for the “raw material” and selection. For example, when I was doing Estate, I had collected a lot of material associated with my condition at the time of the work, but only part of it was used in the film.

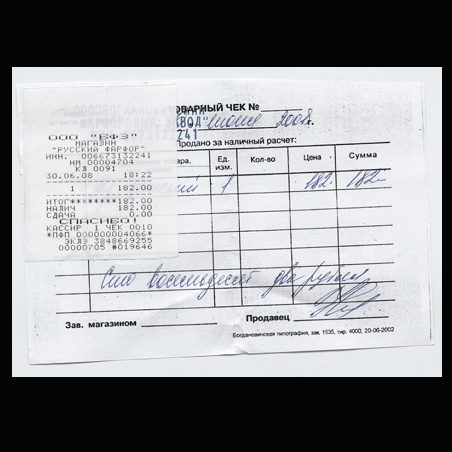

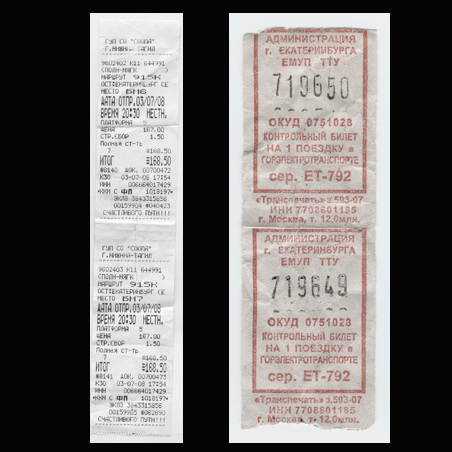

Though, such artifacts such as, for example, receipts, tickets, travel fares, etc., show what artistic process is made of. Some of these things were later included into my catalogue which describes the evolution of fiction.

For example, I worked at the film The Capital about the visually impaired. I had dialogues with these people via a typewriter: they typed their answers. I have these documents. Often I show these artifacts along with the movie. For example, I do installations which are either an independent work, or a prologue to the main work.

You left Belarus in 1989, but you call yourself a Belarusian artist.

A.К.: For me it rather means “an artist from Belarus”. I don’t imply any other meanings. For example, many German artists, who now live in America, say they are from Germany. Although in reality, these questions no longer arise within the international art community. Many artists deliberately avoid specific definitions, because they pursue other goals. For example, to compare the notions American Artist and American abstract art would be rather an attempt to get hold of capital, which used to exist in Europe, and the promotion of national identity.

There is a book called “How New York stole the idea of Modern Art” (“How New York Stole the idea of modernism”) which describes the golden age of abstract expressionism not only in terms of artistic movements, but as part of a particular political agenda. The label “America” is used as something completely exclusive. This was the beginning of the Cold War. A lot of artists who supported communist ideas and worked within socialist realism lived in New York at that time.

Then, how come that abstract expressionism became the main art stream in New York in the 50’s?

Can we say that today nationality is rather a limitation for the artist? Especially if you were born outside the EU or the U.S., and therefore, face with at least physical boundaries?

А.К.: This would be a too simple answer. Nationalities consist and are constructed from various aspects and thus add a certain value to self identity and to self identification within space and culture. On the one hand, these concepts have been formed and worked for centuries in the Western European space, and now there is the awareness of the values of the European Union. In contrast, at the time of nation building in other post-Soviet countries, communism had been built, but the process was not completed. Therefore, as a result everything got back to the 19th century. Due to this fact, such forms as language, topography and tradition have become very important. Most likely, post-Soviet countries have to go through this stage.

But on the other hand, it is a step into the past, and need to look into the future. Therefore, I think that the national can both limit and expand, depending on what approach to use.

The globalization of modern society is evident. However, you made the project 35 Grams, you shot the film Palipaducienne and made a glossary to it. So, it means that this issue is not solved for you?

А.К.: 35 grams is, actually, a rethinking of those boundaries which the artist is experiencing not only in spiritual terms. This is something that is left unnoticed, all that globally existing bureaucracy that affects a person physically. No matter which country you are from, what your nationality is, there are still barriers and bureaucratic obstacles which have to be overcome.

35 grams is how much a passport weighs. It’s a trifle thing. But if to think about emotional and spiritual state, which affects a physical state, it’s very important.

Every time one crosses the border with the Belarusian passport, this “35 grams” kill great deal of time. To be issued a visa, one first needs to get a medical certificate, income proof documents, explain the purpose of the visit, etc. And even after all this procedure, it is not clear whether the visa will be issued or not. If it is finally issued, it will be a short-term visa. So, uncertainty again. Then there is another performance at the border where one has to confirm their identity, etc.

How much does your passport without any stamps weigh?

А.К.: 30 grams.

This means that 5 extra grams defime my Belarusian identity. I’m a “naked body” without these five grams. But this project is not about how difficult it is for Belarusians or Eastern people to travel. It would be too primitive.

My goal was rather to show that my time as an artist is also planned in these bureaucracies, namely, by the countries which sign agreement on the identity and nationality. This “soul”, namely, 35 grams, is present in each of my work, even if I’m working with a different theme. This is my task as an artist: to decode the phenomena encrypted by the system, and to try to open the artificial environment built up around a man.

You’re talking about global processes and your interest in them. However, in your next films you are discussing the topic of the Belarusian language.

А.К.: In our country, language has always been very politicized.

It has been fighting for existence, but nowadays there are different kinds of discussions. I would like to switch focus from my personal opinion to reality. I wanted to reveal as many ambiguous concepts as possible.

So I decided to talk to Belarusian emigrants who identify themselves as Belarusians despite the fact that they don’t speak Belarusian. I decided to have a look at the constructive side of the language which is more related to poetry, to the so-called avant-garde. Can language be something else, can it identify anything? What features can it have? Upon emigration, the language is perceived not only through the identity or communication; it is reduced to the functionality of sounds and memory.

Thus, in my films language is used to raise the political, social and cultural issues. My works explore the political aspect of the language. They investigate how the language creates an individual or collective experience. The project also addresses the impact of language policy, when the official language contributes to the national unity. At the same time, the films tell how the acceptance or rejection of the experience of language strategies becomes a form of resistance. Language manifests itself as a weapon or a shield that can protect, hurt or defeat.

When you were making a presentation in Minsk you said that the artist today existed in the information context. What is your information context?

А.К.: Surely, there is context around me. But work and creative work means a constant creation of a new context as well as answering this context. One can shape their own contexts, their own environment, or fit into the existing one and work with it. One can criticize context. For example, facebook: if you’re not registered in it, you are viewed as an asocial person. This is also one of the f information flows where you are not the actor, but the viewer and consumer.

Every day I read the news; there was a time when I read it non-stop: in the morning, in the afternoon, and in the evening. And I didn’t care where the news came from. Boris Groys wrote that

nowadays the artist has also become a consumer: he does not create, but uses; he takes artifacts and changes them into other artifacts. Therefore, the context of news had for a long time been my context.

Now I’m trying to extend this context a bit, for example, to read books, communicate with people.

Special for pARTisan, Minsk—Berlin, 2012

Photo by Aleksander Komarov / aleksanderkomarov.com

Opinions of authors do not always reflect the views of pARTisan. If you note any errors, please contact us right away.