Аўтар: Taciana Arcimović, 03/04/2014 | ART interview

Michail Hulin: A Right not to live in underground

pARTisan #25’2013

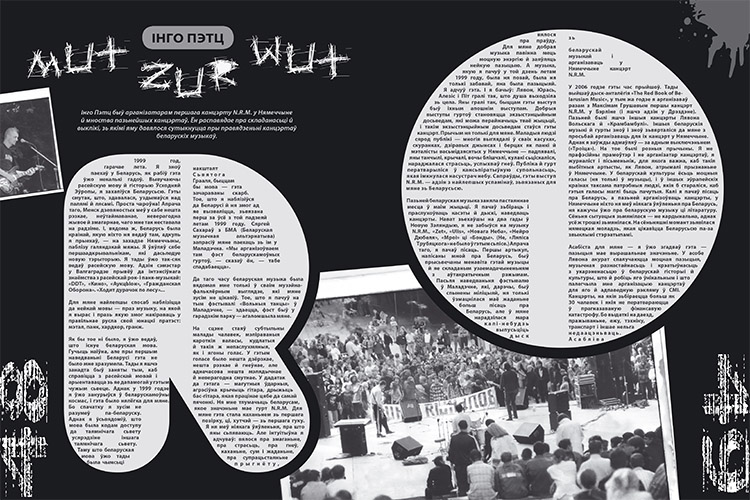

In October of last year in Minsk took place Belarusian part of the international project «Going public», organized by the Goethe Institute. One of the participants of the project, the Belarusian artist Michail Hulin (Mikhail Gulin), made the action Personal Monument: he with volunteers made an abstract sculpture composed of three cubes in Minsk’s central squares and photographed it. On the last point − Kastryčnickaja Square − the policemen asked them the pass and taken away to the department without specific reasons. Afetr that the policemen wrote that Michail with gays resisted during the arrest that’s why they should pay a fine. There was a court where Michail with gays were acquitted because the video from the square showed that there was no resistance of the artist and the volunteers.

Nevertheless, this action indicated how even the most simple, primitive forms in the context of time and place can instantly expose all the political and socio- cultural issues and be an event on a national scale. Some experts noted that this is probably the most successful action of the project «Going public», because it could really find the problem spot.

About difficulty to speak out publicly in Belarus, about his personal experience, and that is why he is not engaged in political art, says Michail Hulin.

Michail Hulin, Personal Monument action / Minsk 2012

Michail, why are you interested in working in the public space? Because of the environment?

Michail Hulin: We made our first joint intervention with my wife Antanina Slabodchykava in 2005 . Up to that moment, I had, of course, heard of the projects of other artists. These were not only Alies Puškin’s actions , but also those ones of our academic students. For example, Aliaksandar Niekrashevich repainted plaster statues of pioneers in a different color; others sculpted out of snow a two-meter long dildo in front of Belarusian Academy of Art. But a clear understanding and a change in my artistic tactics happened in 2008. I came back from a residence in Prague, and realized that it was no longer enough for me to work with one dimension of the canvas or paper. Another important aspect for me is unpredictability which work with the public space gives.

Today, the concept became a dominating power in contemporary art, and many things have turned into mathematics: the artist comes up with an idea, justifies it, and then comes only technical implementation. This predictability has become a burden for me: there was no risk; it all became too rational. The situation changes dramatically as soon as one begins to work with the environment. In addition, the context of a place plays a huge role. So, there was a shift:

I wanted to have a live contact with the audience, unpredictability and I also wanted to become an object of art.

What are the peculiarities of our urban environment? Does it change?

M.H.: Surely, the environment changes, and these changes were happening right in my sight. For example, it’s been five years, but many things that seemed radical to me then, are now just impossible to perform. They should have been done then, but I put them off. I thought it was too radical; I should have waited a bit to feel the environment.

For example?

M.H.: A series of my actions I’m not a … was to begin with the action I’m not a KGB officer. Like an exhibitionist, I had to go outside with dark glasses on, open wide my black coat and show this label. Now it’s too risky. Or, for example, even back then I wanted to make one of my actions on Kastryčnickaja Square. Now this place is so much tabooed and strictly guarded that it is virtually impossible. Who would have thought that in 5 years time, the cyclists would be put on the ground face down?

The environment changes greatly, but art still finds loopholes. Though, I guess I will have a break.

It has become very complicated for me to perform actions because I don’t understand why and for whom I can do them. I don’t see any feedback from the Belarusian environment.

But you last action Personal Monument got a lot of publicity, by the way.

M.H.: Yes, there were a lot of comments, both positive and negative. Someone viewed it as a PR action and accused me of being irresponsible, because, well, a volunteer was beaten because of me. Or they’d say why I should get indignant when I was exercising political art. But I always refuse to call myself a political artist. It’s not because I don’t create political art, but because I’m ashamed. I don’t think it’s an effective tool of political struggle. I do not want to lighten up the pathos and say that I’m changing anything. I think that today an artist is unable to do it.

Michail Hulin, Ich bin kein Partisan / 2008

What can an artist do then?

M.H.: To get rid of pathos at least.

We won’t feed African kids; we won’t change a political situation. Why won’t? We won’t do it, until people want it.

Until there’s a global feedback. My break is partly connected with the fact that I don’t know why and for whom to do it. Is it worth it that volunteer Vład had a concussion? I was actually surprised that this incident was discussed and media wrote about it. They shouldn’t have beaten the guy only because he had helped me bring the cubes! That’s the main thing! There shouldn’t be a discussion what it was − a speculation, provocation or betrayal. By this action, I didn’t offer the viewer any manifest or scenario.

I just tested the space. But even in this simple action, the viewer failed to notice the problem.

Maybe it’s a problem of our time. I think that now it’s impossible to do the same thing which Ales Puśkin had done in the past. It’s impossible neither technically nor ideologically. He wouldn’t enjoy that much support now as he had had then.

What reaction should a viewer have so that you would understand that it makes sense?

M.H.: It’s hard to say what. It’s easier to say what reaction should not be. For example, my most recent work has shown that the institution is placed higher than the artists, because the Goethe Institute in Minsk, like the Polish one, is the only two partners for the alternative Belarusian environment. Another thing, which we recently discussed with Siarhiej Babaryka, is solidarity, which we have none. For example, now in Belarus there is a left movement which often criticizes the neo-liberals. But it’s silly at this stage, I think. Until a stimulating environment for the variety of opinions is established, it doesn’t make any sense for communists to fight against neo-liberals, anarchist against communists belonging to any platform: nationalistic, anarchist, or liberal.

But many people don’t understand it. Then I realized that no one wants to take risks, to really do something. Recently I spoke with another artist, he says there’s no need to be a hero, it’s enough just to talk about it. And I’d agree with him. That is, the Internet environment allows producing fakes, creating a simulation activity. Facebook or Вконтакте (Russian social network) Friend stream replaces the reality. This is why many artists are thinking, why cut themselves if they can draw in Photoshop? But for me personally Actionism means honesty.

Michaił Hulin, I’m not a gay / 2008

Is there an artist who could be a role model for you?

M.H.: It’s difficult question. There are none among the actionists. I don’t like the situation in Russia, but we are better informed about it. I don’t like it because what they have are just bubbles. As regards Europe, there isn’t much happening there if it comes to individual works. Working with the public space resembles the organization of mass events.

The movement Occupy has raised many questions, at least for me personally. I read an interview with the activists who Żmijewski had invited to the Berlinale. I asked them if they had established any contacts with other artists who took part in the Berlinale. They said no. And I understand why. Because for many artists the result is important, while the activists only care about the process. They are asked, guys, what have you done? «We occupied the Deutsche Bank, walked round with posters and interfered with bankers’ work». You’d better had cleaned the streets! So, for me it’s an absolutely meaningless way of struggle.

I was once told that the cubes wouldn’t have worked in Berlin.

But it’s exactly work with the place. At some place it’s better to sing in a church, in another one it’s better to use cubes.

In Berlin I’d have done other things. For example, in Warsaw where the problem of new Nazis is very acute, I arranged an action I’m not a Jew. It is often said here that Belarusian art is secondary, Belarusian artists don’t do anything new. But I wonder, does anyone of Belarusian critics are able to feel a new phenomenon? Or do they only know how to evaluate according to the existing criteria? At the exhibition Zero Radius (Minsk, 2012), for example, each annotation about the artist said that he or she perfectly fits in the global context and is recognized worldwide as a label of quality.

Wait, an artist cannot quite fit anywhere, and still make a powerful work!

For example, it is hard to say how work and art of Alies Puškin fit in the global context of contemporary art. But he made two pieces of work, a white-red-white canvas and A Gift, and that’s it, it’s enough if to speak about the works that define the time.

Exposition of Radius Zero project / Minsk, 2012

How did you come up with the idea of the series I’m not a …?

M.H.: I was going back from Prague on a train with one person. It was a Czech businessman who had a business in Belarus. And I realized that I was afraid to talk to him. He made me feel alert: he was very talkative and changed the topic to politics. And then I realized what my phobia was about. The main thing that became clear is that a question that my fellow traveler could be a decoy passenger simply could not be raised by a free man in a free country. Thus came the idea of I’m not a KGB officer. But I began with I’m not a partisan. For me, it was an important negation.

This is a right to the city, a right not to live in the underground.

I know that our progressive art community lived that way, and I think that even now we are in a kind of underground. I still can’t exhibit my works at other places. I’ve been told to go to the Museum of Modern Art. But I know there will be problems. Y Gallery has actually become the only place for people like me. This is my space. So, the interventions to the city are important to me: I do not want to limit myself to certain frameworks. So I began with I’m not a partisan. Bruised, with this board across my neck, I walked barefoot across Kasryčnickaja Square, then along the avenue up to the Independence square. There was an opening of some exhibition at Y Gallery then, and the intrigue was whether I would come back or not. I did, but no one even came up.

You have worked in different cities with different spaces. What special feature of our city would you note?

М.H.: I won’t say anything new, many people note this feature of our city: it is clean and sterile. But it’s not fucking mine! I mean, formally it looks as though everything is possible, as if everyone has a right to the city. That is, as though nothing is banned. But in practice, everyone understands that this is not the case. My action Personal Monument clearly demonstrated that, well, you cannot go to the Kastryćnickaja Square with cubes, even if it is not banned in any documents.

Then ban it officially so that everyone could know that it’s not allowed!

Let’s ban walking, riding a bicycle in a group of more than there people. I was told afterwards that I had known in advance how it would end. But form my previous experience, I knew that it could have ended differently. For example, when I was carrying my A Hole around Minsk, no one came to me even once. Surely, I could have asked for permission. But we know that in 99.9% of the cases one gets an unjustified refusal. It’s a refusal at the level of «Why do it? We don’t understand»! Recently I applied to the competition named after Malevich with a performance and an action. I was refused. Why? As it was later explained to me, nobody had voted for it. What for? One hangs a painting on the wall and everything is fine. Why have any actions or performances? Actions sound suspiciously.

That is, the artist should be very careful when saying that he wants be engaged in Actionism because it will immediately be perceived ambiguously.

Still, you intend to continue work with the public space, don’t you?

M.H.: Yes, I do. What I’ve just voiced is more a reflection of my experience. Because this, in fact, was my first experience of work within institutional frameworks, and I got messed. Previously, I did all my actions myself and uploaded them to YouTube. Now I understood, for example, what it means to make an institutional project. In Klaipeda , for example, I had to give up a project with graffiti, which I’d proposed. I was well explained why: in such kinds of projects it’s better not to touch upon some anarchist manifestation or controversial issues. It must be a digestible product for all parties. Basically, I understand it.

Now I want to try to do a classic street art, classic. Not a decorative, surely, as most people like. I mean the very intention of young people to first agree with the housing and communal services how to paint a transformer vault. It’s impossible! Street art is a protest thing, I have it in me; I want to put my signature and I do it. Or it’s preferable to stick your picture exactly in that place where it is not allowed to. That the best thrill! What housing and communal services!

Michail Hulin, HATE BAM / Minsk 2014

But it doesn’t mean that I’m only interested in the protest kinds of art. I’m trying not to focus on it only not to lose the sharpness of vision; otherwise you’d be only capable of making one kind of things. I like the moment of surprise, as it was the case with A Hole when it didn’t work for me. Nothing was happening. Even the most primitive, namely, the conflict with the police didn’t happen. And suddenly came that woman, and it all came together, and the conflict was no longer needed. I think now in hindsight, well, we were with these cubes at Kalinin Square, at Kolas and Niezaležnasci Squares. Perhaps, we shouldn’t have gone to Kastryčnickaja Square at all. And now I realize that, perhaps, for the institutional project we shouldn’t have, but for the inner feeling of the artist — yes, we should. Because only then the line builds up. How could it left be without the finale?

Though, it wasn’t a pure action. I tried to ingrain my own planned things in this project, because, actually after A Hole I came to realize that the peculiarity of my Actionism is portable objects. That is why the cubes appeared. I’m not for the decorative art and communicativeness as such. I am for conflicts with the environment; I am for the collision with the audience.

In this regard, Belarus is a real godsend for the artist!

M. H.: Yes, I absolutely agree. There are moments that one can work with, and it’s fun. The only thing is that one need to get the answer why and is it worth taking the risks? Actionism in itself implies certain energy for a radical gesture. Each actionist comes to a point: here I am and will do such a thing! But in fact, the main thing is to seek the truth and not just do something loud.

Heroism is not honored in Belarus, its place is vacant. I don’t think we will see a Belarusian actionist soon.

Minsk 2013

Translated by Sviatlana Sous © photos by Michail Hulin

Opinions of authors do not always reflect the views of pARTisan. If you note any errors, please contact us right away.