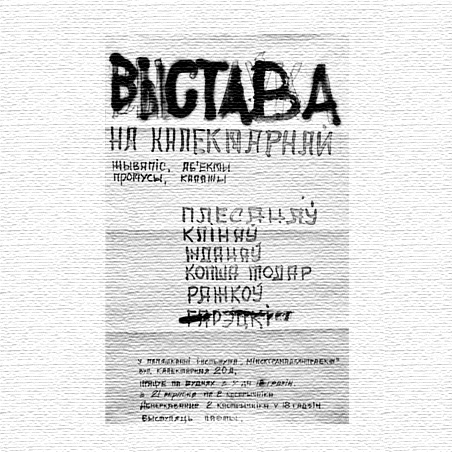

The announcement of the Exhibition on Kalektarnaja Street \ 1987

«pARTisan» #3’2004

Alaksiej Źdanau near Minskprajekt \ Minsk, 1987

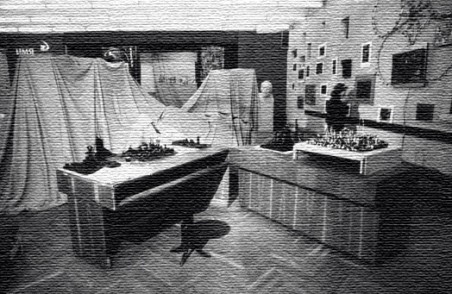

The Exhibition on Kalektarnaja Street \ 1987

The Exhibition on Kalektarnaja Street \ 1987

The Exhibition on Kalektarnaja Street \ 1987

The Exhibition on Kalektarnaja Street \ 1987

On the foreground The Portrait of the Patriarch by Vital Ražkoŭ

Artur Klinau on the exhibition \ 1987

Archieve © pARTisan #03’2004

It was in 1987, soon after Mikhail Gorbachev had become a new leader of the USSR. He was smart, had a birth-mark on his forehead and well-educated wife Raisa, admired in the west. Moscow plunged itself into a new life.

Yet, in Minsk perestroika sounded meaningless.

Local authorities were dragging their feet over it. After all, Minsk was only a province, with all the old communist party bonzes still in their places. They were still standing firmly on their feet of clay.

One fine autumn day a friend called on me for a cup of tea. Her name was Ludmiła Karatkievič, she was an architect and had worked at the Minskprajekt design institute in Kalektarnaja Street for 20 years. The Minskprajekt was a kind of military enterprise, where all employees were disciplined to start and finish their work by the bell. Having been kept at this concentration camp for 20 years, poor worn-out Ludmiła dreamt of taking revenge on her dear Minskprajekt.

‘You know what? We’ll hold an exhibition of avant-garde artists there!’ I said.

‘It’s a brilliant idea!’ said Ludmiła.

The next day extravagant and vigorous architect of Jewish origin Ludmiła Karatkievič turned up in the office of the Mienskprajekt Young Communist League. A black man’s hat, blood-red lips, beautiful brown eyes, full of deep inner commotion mixed with languor, she approached their leader with the most innocent proposal.

‘Let’s have an exhibition of young avant-garde artists on our premises,’ she said.

‘What does ‘avant-garde’ mean?’ said the naive young communists’ leader.

‘Avant-garde artists are those who paint best,’ Ludmiła did not bat an eyelid as she gave the answer.

Actually she had never seen any Minsk avant-garde artists herself, for those odd birds were kept away from people’s eyes.

So in the evening dissident poet Alaksiej Ždanaŭ and I discussed the participants. Vital Ražkoŭ was a young artist, who had graduated from Minsk Art School. He seemed a bit stand-offish, wore a long white mac and had a reputation for his extreme radical views and actions. Andrej Plasanaŭ had a versatile personality. A singer and a painter, he also played musical instruments, wrote texts, collected cards and antiques. We found his leeway suitable.

Todar Kopša was a professional artist and a moderately nationalist aesthete. Artur Klinaŭ, a young painter, always caught everyone’s eye and was always setting right his glasses, which would slip off his hawked nose, and describing how he had come back from Petersburg the previous day.

Alaksiej Ždanaŭ was a poet much known to the chosen few, who looked like a retired wrestling coach, though he actually hated any physical activities. He wore glasses and had been studying philosophy at university. Alaksiej had spent all his life painting some cranky pictures of crazy aliens and making collages with Stalin and Lenin along with their victims.

Once I heard a tale from a three-year-old kid, who had seen the poster Lenin Wearing a Cap, ‘Once upon a time there lived Lenin. Then he died. So people now say on their way to work, ‘Bye, Lenin!’ This was very close to the impression you got from Alaksiej’s collages, where among other things Lenin had lipstick on his mouth.

The Minskprajekt assembly hall looked typical for the socialist epoch – rows of chairs, a stage with a table covered with a red cloth and the inevitable white plaster bust of the immortal dead man. ‘Bye, Lenin!’

On Monday morning Kalektarnaja Street saw the opening of the avant-garde exhibition. There were papers tacked up all over the walls and covering the floor. The chairs were arranged in a huge pile in the centre, naked human limbs randomly sticking out of it. Vital Ražkoŭ had borrowed them from the Miensk Prosthetic Factory. That installation of his was entitled Perestroika. To the left of the door, there was The Portrait of the Patriarch by Ražkoŭ hanging on the wall. It represented naked Brezhnev as an old fogey with enormous private parts.

After a short debate it was decided to cover them with a coquettish scarf, which was promptly nailed to the canvas. Now it looked even more amusing.

To the right of the door you could see Plasanaŭ’s slightly erotic paintings of astronauts in protective suits. Further on came delicately aesthetic abstract paintings by Todar Kopša. The space next to the stage was covered with Alaksiej Ždanaŭ’s collages. To see Artur Klinaŭ’s canvases, you had to get onto the stage. They were striking indeed, especially Death in Kastryčnickaja Street. There was a dead cat in the middle of a narrow winding street, but it immediately reminded of Solomon Michoels, the director of the Jewish theatre in Moscow, who had been run over by a lorry on Stalin’s orders in Kastryčnickaja Street in Minsk.

All in all there were quite a lot of Artur’s works, the largest entitled The Revolution. It was clear they were painted by an outstanding artist with a remarkably strong individuality.

Early in the morning the Minskprajekt door opened to let in its slaves. We were all eager to meet our first visitors. At last several people made their first steps to enter the exhibition hall and… stopped there, petrified, one leg raised in the air, just like herons.

They did not have the guts to step on the papers! Being official mouthpieces, the papers on the floor paralysed the architects with fear!

The people were scared to walk on the papers with photos of the Politburo members. It was an unforgettable sight. Finally, they plucked up the courage and came in. At first they stared at the exhibits in silence. Then, having cautiously looked around, they peeped at what was covered with the scarf and burst out laughing. Especially ladies. Or burst with indignation. Those were veterans, of course. Opinions split drastically.

About a dozen visitors had turned up before lunch-time. They were the first to have ignored the bell. After lunch, when they had shared their impressions with the others, there was a whole crowd willing to see the avant-garde exhibition.

On Tuesday the exhibition hall was swarming with people. The Minskprajekt institute was not functioning. The architects were strolling along its corridors, discussing the exhibition.

On Wednesday morning the exhibition was attended by the Communist Party City Committee delegation, led by the head of the culture department and the ideology secretary. When Ms. Ivanova, the head of the culture department, saw Alaksiej Ždanaŭ’s collages with Lenin wearing lipstick, she fainted. Having come to her senses, she said to Alaksiej, tears in her eyes,

‘You have insulted a woman in me’.

‘I haven’t,’ said dignified Alaksiej Ždanaŭ, with a twinkle in his eye.

The ideology secretary started lecturing Alaksiej.

‘Speak up,’ said the latter.

‘Can’t you hear me?’ the ideology secretary got offended.

‘No, ‘cause you have the 1937 victims’ blood in your shoes,’ said Ždanaŭ distinctly.

The secretary said nothing more. We all felt the exhibition could have been banned. Alaksiej Ždanaŭ had an acute pain in his heart. Vital Ražkoŭ offered to stay overnight in the assembly hall. That was very thoughtful of him, as the authorities had the locks changed at night, so the next day Vital let us in from inside. The hall was packed with people. But this time you could spot plain-clothed KGB boys in the crowd.

The architects were victorious. No-one was working; no-one took any notice of the bell. On Thursday night we were informed the exhibition would be closed down. The situation called for immediate action.

‘No way. I’ll go and send a telegram to Raisa Gorbachev,’ I said.

The telegram read, ‘Dear Mrs. Gorbachev, young avant-garde artists have opened their first exhibition in Miensk. But the authorities are going to ban it. Please, save our exhibition’. I believe she did receive the telegram. The exhibition was not closed down, owing to Mrs. Gorbachev, may her soul rest in peace. But the party bosses ordered the assembly hall to be redecorated.

That was the climax of the whole thing! There were gaping holes in the floor. A welding machine was showering down sparks. The visitors were being whitewashed. It was all like a picture from hell. A feast of absurdity! Perestroika was advancing!

‘You know what perestroika is all about?’ asked Alaksiej Ždanaŭ. ‘There’s, say, a bowl of shit in the house. It has a lid on and does not bother anybody.

Then someone puts it on the cooker and starts stirring. Imagine how it stinks! This is perestroika.’

Ludmiła Karatkievič did avenge on the institute she hated! Now that eighteen years have passed, I am still proud of that smashing exhibition. For years since then, art censorship in Miensk had been dead. After Kalektarnaja, you could exhibit whatever you wished. This was what we actually fought for.

The freedom to step on newspapers is worth it.

Natalla Tatur, Warshaw 2004

Translated by Volha Kałackaja

photo © pARTisan

Opinions of authors do not always reflect the views of pARTisan. If you note any errors, please contact us right away.