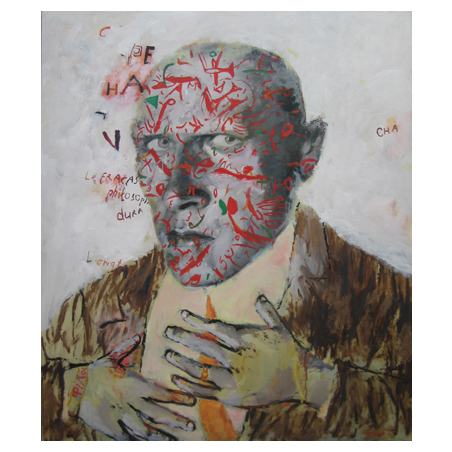

Igor Tishyn Philosophe

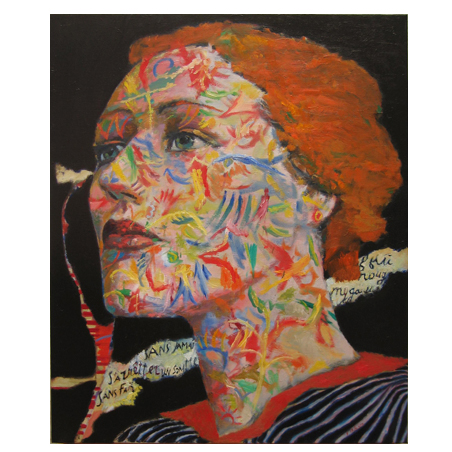

Igor Tishyn Leni

Igor Tishyn 1932

Igor Tishyn Conversation spirituele

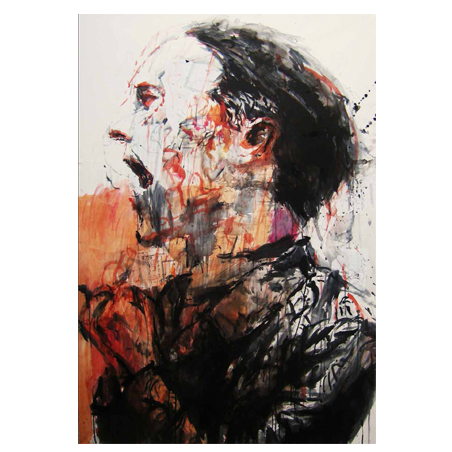

Igor Tishyn Eisenstein.by

Igor Tishyn Rodchenko’s Formulae

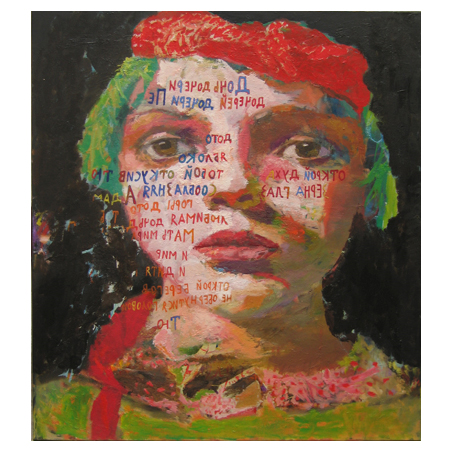

Igor Tishyn Chapeau rouge

Igor Tishyn Chapeau Rouge (Super-8)

Igor Tishyn Futuriste

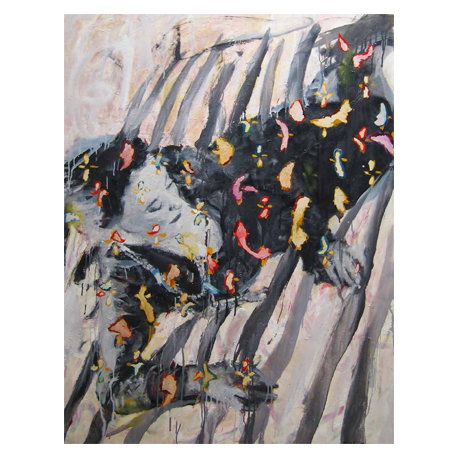

Igor Tishyn Lying. (After Rodchenko)

Igor Tishyn Little Mouse Doctor

Igor Tishyn Untitled

If one tries to remember any by IGOR TISHYN’s works, he or she faces an amazing phenomenon, namely, the memory is as if getting stuck in details, without restoring the whole picture. Some separate forms are rushing to emerge, although there is no full confidence whether they belong to this particular piece of work or any other one, or they are just a product of our imagination.

This is due to the fact that the artistic practice of Igor Tishyn is perceived as a single stream, and no individual replicas can be singled out of it. His sensuous, paradoxical, and rude artistic practice allows us to see the post-Soviet reality through the eyes of history. It has signs that belong to different periods of the history of the twentieth century; it embodies everything that has today been expelled from the official culture, and at the same time known to everyone.

Igor Tishyn is one of the most significant contemporary Belarusian artists. He has been living and working in Belgium for more than 10 years. However, all material, images, scenes and objects for his paintings, installations and photographs remain Belarusian by nature. They are directly related to the post-Soviet realism of 1990s, and to the political and historical aspects of modern time. Not surprisingly that in Belarus Igor Tishyn is to some extent mythologized.

He is called “grandfather of the partisan movement”, and cliché epithets have been assigned to his paintings, for example, “expressionism with a socialist face”.

Meanwhile, there has been no deep research, analysis, rethinking or at least description of his art. His capricious, impulsive painting, half-ironic marginal projects of the 1990s, as well as his gloomy picturesque spells in photography of the 2000s altogether puzzle researchers and take them to the dead end. Any theoretical speculations inevitably become controversial in the face of this brutal, impulsive, and paradoxical art. The theory becomes worthless. Tishyn’s works, being a wild burlesque, laugh at any theories.

History as the operational space

History, namely, the history of the 20th century has always been present in the works by Igor Tishyn. Even when he does not directly reconstruct the past, he still does this at the level of articulation, combining different styles from the history of visual art, such as “severe style”, compositional allusions of Futurism and Constructivism, Arte Povera, and art-brut. Alongside, he is often simulating profane or outsider art.

This mixture of styles is clearly seen in his works Rodchenko’s Formula (1995, 1999), for example, where the constructivist pureness of photographs is diluted under the influence of pastose painting. The historical perspective of Tishyn’s works and actions of the 1990s is reinforced by the use of archival “family” photos as well as an obvious reference to the Russian avant-garde of the first quarter of the twentieth century. Tishyn’s manner of painting in the 1990s, originates, in fact, from those days. It is balancing on the verge of profanity and experiment. Futurists, whose practice he refers to, painted like outsiders, partly relying on folk popular print tradition, and Russian icons. This is where early Tishyn’s combination of text and images in painting comes from, such as his work Raja is a Futurist (1994), which can be compared in style to the works by Burlyuk, Goncharova, Kruchenych, Rozanova, Larionov and others.

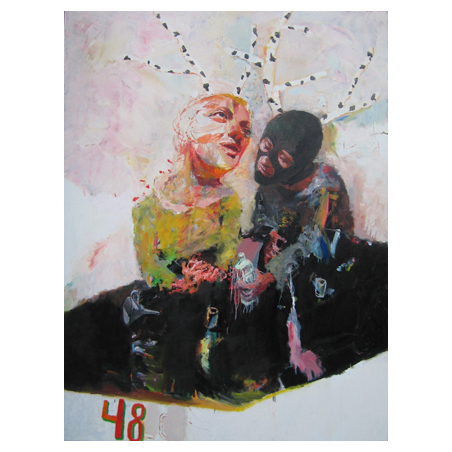

Only later in 2000s, Tishyn’s art acquires an active expressionist coloring. But even then, the connection with the early Soviet era is supported and emphasized due to numerous cultural and historical quotations, such as references to the futurists, pathos of Stalin baroque, as well as quotations from Mayakovsky and Khlebnikov, and others. Also, very often his collages and paintings contain the dates 1932, 1944, 1948, 1989, etc.

Thus, the reality in his paintings always emerges from the fragments of the past. Though, it cannot be otherwise: as new era comes, past does not disappear. It is not just only present in our memory; it is drifting both in our minds and our perception.

Obviously, personal biography and experience of living on the verge of two epochs play a crucial role in Tishyn’s artistic work. In fact, in each of his works we can observe an effort to understand the socio-cultural reality, which has been established between the two world wars, and connect it somehow to the present. This is the time when codes of perception and self-perception used to define people’s relationships with each other and with the world have been shifted to some unknown dimension, and have only been defined by the ideology of newly built socialism.

In the 1980s, the period of “developing socialism” was already over. However, by that time, morality, aesthetics, politics, economy, and the needs of the whole generation underwent a profound change. In the mid-90’s, it became clear that the «independence” gave this generation neither a long-awaited completeness of life, nor real freedom. In this period, the artist made such actions as Mobile Exhibition (1995), Light Partisan Movement (1997), and A Phallic Frau (1997). In all of these actions, Tishyn worked with the specifics of the places, shattering the space and at the same time establishing a dialogue between the objects and the environment. As a result, he came up with spatial compositions where color, texture, and history of objects act to evoke a semantic meaning and synesthetic experience. This was work with materials, household items and clothing found in abandoned houses which evoke many associations and memories. Not in the least, it was work with gender and policy issues. Also, it was work with private and almost intimate family stories.

We have an example of artistic practice whose function is not to express or say something, but rather to state the invisible reality, history, which we are not aware of, and our part in it.

Many-layered walls in Light Partisan Movement can clearly illustrate this. Layers of wallpaper, one standing out from under the other, plaster and bare brick is a kind of decollage or a new Belarusian palimpsest. When the viewers see those photos of particular situations which happened, perhaps, decades ago, against this background, there appears the effect of transparency of history. Also, there is an impression that different historical events have taken place simultaneously.

A peculiar feature of these actions is that they are united by a common theme, namely, the taken off items of clothes and naked bodies. A possible way how to interpret this can be found in the ideas of Lyotard about “the others’ rights”. According to Lyotard, a naked man is an apolitical person. He doesn’t have any rights. To receive any rights, he has to become something else other than a human being. This something else has gone down in history as the notion of “a citizen”.

Thus, the installations A Phallic Frau and Light Partisan Movement indirectly bring to life the issues of civil rights and political aspects of the issues of the private and the public, which will be discussed later.

In his actions of the 1990s, Tishyn manages to portray history as a movement of a functional front which combines different timeline events, situations and ideas into one stream. At the same time, he manages to doubt the role of art and art institutions in this conflict space.

Need for imperfection

Although sometimes many of Tishyn’s works can resemble hallucinations, they nevertheless possess the density, thickness, and physiology. A restless character of his optics, rude, “uncombed” manner of expression and his choice of heroes and heroines give his art a character of degradation. His world is degraded.

His characters are deformed (or formless) beings, either tense or relaxed, namely, girls in school uniform, the homeless, prostitutes, masked alcohol-producers, as well as literary and historical characters.

His stenography is abandoned interiors, dirty yards, chipped walls, disorder, incompleteness and troubles. Everything is wretched and shabby. A secret Belarusian need for imperfection, incompleteness and formlessness finds its expression here.

This decay of reality is most evidently portrayed in the series Crisis in Paradise which combines infantilism, coincidence and a monstrous face. Carts, old stoves, destroyed houses, and abandoned yards − all this inspires Tishyn. More than 20 photographic images in the series Crisis in Paradise serve as a basis for artistic intervention. The artist paints deserted interiors in wooden baulks and piles which, in reality, don’t support anything. In the yards with various household items scattered around, some strange biological creatures are materializing in the air and add a frightening dynamics to the picture.

A skinny wolf is wandering round the empty streets on stilts. This all is not clear, and since it is difficult to name or define it in any way, it is frightening.

His paintings look like fragments of one and the same nightmare. But the strangest thing about this situation is that the contrast between visual art expression and photographic actuality looks very organic in Crisis in Paradise. Tishyn’s visual attacks are as if engraved into the portrayed environment. They creates the effect of irritation, since the viewers get the illusion of a complete realism of what they have seen.

In the series Visio beatifica this decay of reality causes an explosion. What is this? Infernal apparitions in the middle of everyday life, or hell, which is a part of everyday life? In both series, the basis for his artistic intervention is photo-images. Tishyn adds a second mystical layer to the really existing space, thus revealing the dark side of our reality. Dark sarcasm of the name of this reality indicates that the strange, painted in oil formations, which look like bomb explosions, should be perceived as a form of transcendental vision (Visio beatifica is a theological term which means a supernatural act of the ultimate direct self-communication of God to the individual person, when she or he reaches, as a member of redeemed humanity in the communion of saints).

A book of sketches “A Sutin’s Line”

The book of sketches “A Sutin’s Line” is a collection of often short non- related notes on book margins which were made during 2007-2012. This is a sort of a diary where one can find the majority of plots, story lines and motives of many works, installations and projects of different time. Previously, we have discussed different styles and eclectic character of his art and actions where the author used the experience of futurism, constructivism, expressionism, art-brut, and Arte Povera. However, the book of sketches has none of it. It has one form, and its general mood reminds more of Rembrandt and Goya’s drawings, and, to some extent, Emil Nolde’s.

If to remember how Lévi-Strauss compared painting to articulate speech, then “The Book of sketches” is like a story told in a loud voice switching from scream to growl and then a whisper.

As any story, it unfolds in time. The time means five years while the content of “The Book…” was enlarging. There is the axis of narration and the axis of comparative density. The book is like a big music score where plots and characters are intertwined. Some of them are worth to be described in detail.

The repeated scenes of violence, such as the public flogging, can be considered from the point of view of “eternal evil, eternal justice and eternal punishment”, which J. Rancière altogether calls politics. He explains his opinion via the examples of the movie “Dogville” by Lars von Trier and the play “Holy Johanna from the slaughter houses” by Bertolt Brecht. Both these works, just like works of Tishyn, picture violence, and persecution of individuals by the crowd. “Christian morality is useless to fight against the violence of the economic system”, says J. Rancière in regard to Brecht’s play. “It should have been transformed into a violent morality… Thus, the confrontation between the two kinds violence is also the confrontation which entwines the two moralities and two laws. This division of violence, morality and law is called politics”.

In Tishyn’s “The Book…”, like in the two previous examples, one can come across the image of collective, organized persecution, i.e. an act of violence performed by a certain social group.

Such violence can be viewed in the existential sense as the incompatibility of the individual and society. However, one can take a wider look at it in terms of Rancière’s metaphor concerning politics. After this, it is easy to bridge a gap between the topic of violence and the subject of Oedipus, which is often present in Tishyn’s works. A sign of Oedipus always means a forgotten trauma or event. Once remembered, it can heal the wound. If we consider the fact that according to Rancière, a trauma in the area of policy is called terror, then the scene of public flogging can be interpreted as repeated in history acts of oppression. Modern philosophy explains these acts of oppression by the imperative to save a social body enshrined in society. This means that the society is soaked with hidden neuroses, and thus it suppresses and destroys itself.

To sum this all up, it can be said that in his paintings Tishyn expressed the disadvantage of being in the collective irrational and gave the right to vote to this irrational “we”, which in his painting can be compared to “we” created in Andrey Platonov’s prose.

The power of Tishyn’s artistic practice is that he found a unique visual language for the anonymous “we”.

Problems of reception

Little does Tishyn care about giving his paintings an orderly, tangible, and easily seen form. He almost never tries to separate the main idea from a secondary one; he refuses to use compositional ligaments which could clarify the relationship between the various parts of the picture. He uses all means to simplify forms, as well as distortions and change of the scale. Also, the artist continuously varies the style tying together documentary details and chimeras. As a result, the viewers can have a feeling that they see a rough draft or introverted cursive following a spontaneous associative way of thinking of the painter, rather than a ready object made in accordance with a pre-defined plan.

The only thing left to do us to follow the most noticeable words in the stream, the logics of emergence and disappearance of particular topics or connection between some semantic notions. Sometimes the stories are based on found objects, sometimes it is a material, a room, or even a word. Thus, we see paintings which contain different signs. These signs form a certain unity. Sometimes certain cultural knowledge is required to be able to interpret them. (For example, to interpret Leni is A Little Red Riding Hood one should at least know that Leni is none other than Leni Riefenstahl, a film director of Nazi propaganda movies. In these movies, politics was always shown with grand theatrical effects containing “something of a Catholic Church ritual and the legacy of Wagner”).

Other signs in Tishyn’s paintings can be read by everyone, since they all contain emotionally significant values and rather refer the viewers to their connotations. One can remember birch trees which have become clichés in Tishyn’s paintings and are associated with poems about Motherland in school textbooks (A Picnic, A Panoktikum etc.).

Therefore, while studying Tishyn’s art, we should separate the notions of the visual and the iconic messages. Alongside, Tishyn’s works contain also verbal messages that are given to us directly in the form of inscriptions to the paintings and texts in German, Russian and French. These messages are not difficult to decode: it is enough to know how to read. However, they are not as simple as they appear. Sometimes Tishyn writes full texts copying notes from his diary or abstracts from letters. Very often they block the visual image (Organization of a Human Face, A Poet, Geben sie mir …, French philosophy, and others). Sometimes texts appear as a noise, as inscriptions on a fence which are often impossible to read, and thus, are even more confusing to the already puzzled recipient (A Goal, A Futurist, A Philosopher).

Nevertheless, due to this verbal component, the sketches of installation, painting, watercolors and collages acquire a semantic network which allows interpreting them. This network can be described as existential and psychoanalytical.

One can see Sigmund and Franz on one page of A Sutin’s Line; there is also an abstract from “Oedipus And The Sphinx” by Jean Inges, there is Sartre who “miraculously” appeared in a polyptych Mobile Exhibition. Here and there one can see haunting motives referring to a traumatic experience and reference to childhood.

All this forms a single puzzle and gives viewers a hint, namely, a method of free associations which can help to perceive Tishyn’s paintings.

This method has been the main instrument of the psychoanalyst, aimed at decoding the irrational. In order to decode everything, one should only afford themselves to talk freely about anything that comes to mind, however absurd or obscene it may seem, because the uncontrolled associations is a symbolic, or sometimes even a direct projection of the inner content of consciousness. There one can find a parallel with Tishyn’s creative process. Also, it is a manual how to perceive his art.

It is obvious that Igor Tishyn’s works is yet to be studied, whether by the method of free associations, structural analysis, techniques of deconstruction or something else. Now we can only say that his position is a unique phenomenon in the Belarusian cultural space. His art shows us a strong, liberated neglect of all conventions. A personal independence of the artist and whole layers of our collective memory are combined in his paintings.

His work is not only a part of the modern Belarusian artistic process, but also an important part of our historical identity.

Taciana Kandracienka, Ph.D. in History of Arts \ Igor Tishyn. pARTisan’s Collection serias. Minsk’2013.

Translared by Sviatłana Sous.

photo © Igor Tishyn

Opinions of authors do not always reflect the views of pARTisan. If you note any errors, please contact us right away.

Uses of visual materials are permitted and prohibited by the Copyright Act.